Step into the stories that have shaped generations, inspired millions, and changed the way we see ourselves and the world. Join Peter de Kuster-renowned storyteller, and guide-on a cinematic adventure through the 1001 greatest movies ever made. This is not just a film list; it’s an invitation to explore the stories you tell yourself, discover your unique narrative identity, and transform your life and business through the timeless wisdom of cinema.

The Journey: Discover Your Story in the Movies We Love

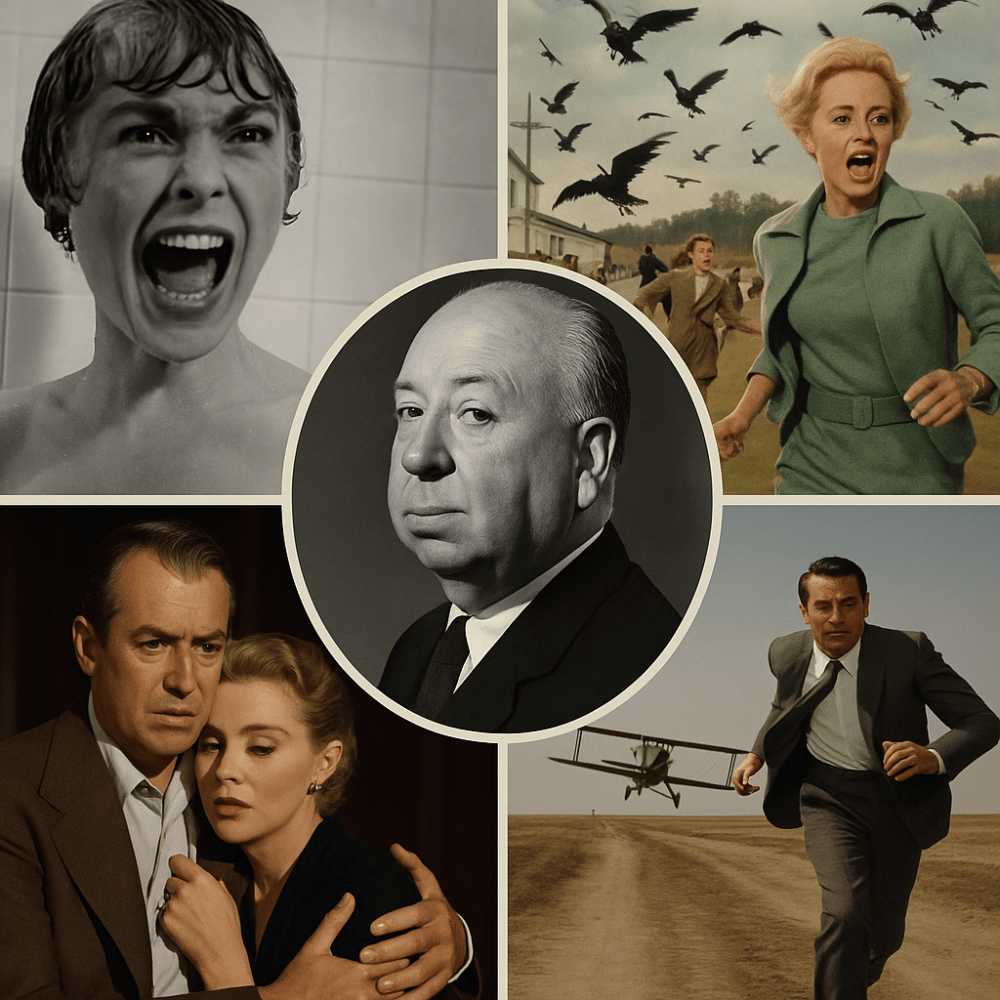

Imagine your life as a film-full of drama, comedy, adventure, and transformation. On this journey, Peter de Kuster will guide you through cinematic masterpieces from every era and continent, from The Godfather and Seven Samurai to Pulp Fiction, Spirited Away, and The Shawshank Redemption. Each film is a mirror, reflecting archetypal patterns and universal themes that play out in your own story.

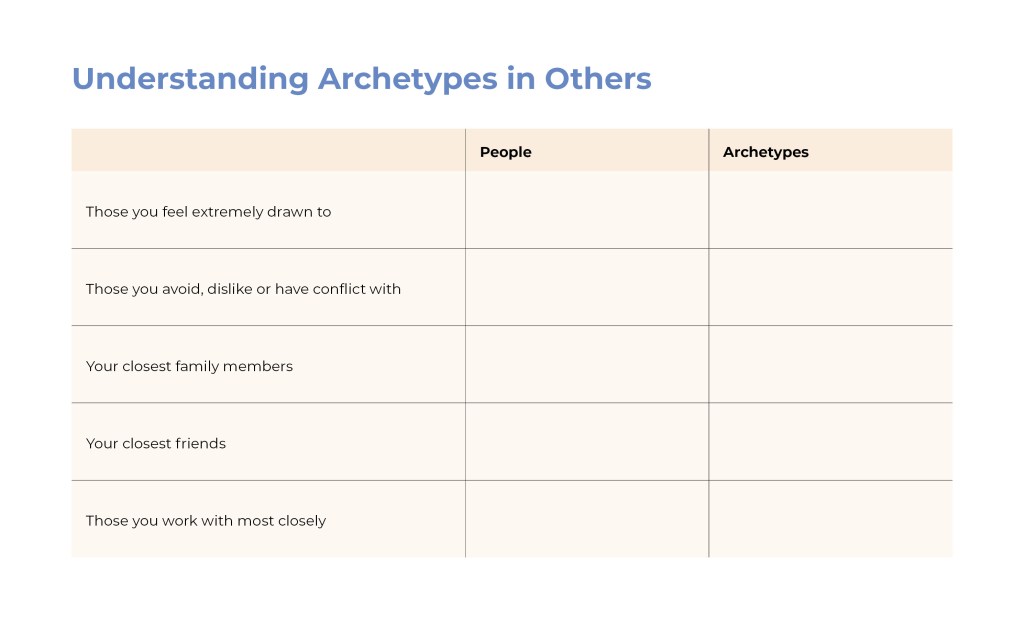

Together, we’ll explore the power of the stories you live by, using the world’s greatest movies as our guide. Through the lens of archetypes like the Seeker, Warrior, Creator, Sage, Jester, Magician, and Lover, you’ll uncover the deep, often unconscious patterns shaping your choices, relationships, and ambitions.

What to Expect

- A Cinematic Exploration:

Dive into the essential scenes, characters, and themes of the 1001 greatest films ever made-from classics like Casablanca, Citizen Kane, and Lawrence of Arabia to modern masterpieces like The Dark Knight, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Parasite. - Personal Story Mapping:

Reflect on your own life as a movie. Which archetypes are you living? Where are you stuck in an old script? Where is your next plot twist waiting? - Practical Story Tools:

Use Peter’s “What Story Are You Living?” instrument to identify your strengths, challenges, and growth opportunities. Learn how to reframe setbacks as plot twists and discover new strategies for self-improvement and creative leadership. - Inspiration for Change:

Let the wisdom of cinema open new perspectives, rekindle your sense of wonder, and inspire you to rewrite your story with courage and creativity.

Who Is This For?

- Creative professionals, entrepreneurs, and leaders seeking clarity, confidence, and meaning in their story.

- Anyone who loves movies and wants to use their power to spark personal or professional transformation.

- Those ready to explore their blind spots, develop new mindsets, and gain feedback in a supportive, inspiring environment.

Practical Information

Start Date: Any Date You Want

Duration: 5 weeks

Time: 4 hours/ week

Language: English

Price: Euro 699 excluding VAT

Book your place by mailing us at peter@wearesomeone.nl

About Peter de Kuster

Peter de Kuster is the founder of The Power of your Story, a storyteller who helps creative professionals to create careers and lives based on whatever story is most integral to their lives and careers (values, traits, skills and experiences). Peter’s approach combines in-depth storytelling and marketing expertise, and for over 20 years clients have found it effective with a wide range of creative business issues.

Peter is writer of the series The Heroine’s Journey and Hero’s Journey books, he has an MBA in Marketing, MBA in Financial Economics and graduated at university in Sociology and Communication Sciences.

Benefits of the Journey

- Gain deep insight into your personal and professional narrative.

- Discover your unique strengths, challenges, and growth opportunities.

- Learn to reframe setbacks as opportunities for growth and creativity.

- Leave with a personalized list of films to watch and reflect on, tailored to your story journey.

- Experience the magic of cinema as a tool for self-discovery and leadership.

Ready to Become the Director of Your Own Life?

Your story is your life’s greatest masterpiece. Too often, we live by scripts we didn’t write. This journey is your chance to become the storyteller of your own legend, using the timeless wisdom of the movies we love as your guide.

Contact Peter de Kuster at peter@wearesomeone.nl to reserve your place on this cinematic journey of self-discovery and transformation.

Peter de Kuster is the founder of The Heroine’s Journey & Hero’s Journey project, helping creative professionals and leaders worldwide shape meaningful lives and careers through the power of story.

Join the founder of The Hero’s Journey, storytelling, mythologist, and tour leader Peter de Kuster on an exquisite exploration of Rome, one of the most sensual cultures in the world. To discover the story you tell yourself about yourself – your life and business – and how to transform this story.

Peter will lead you on an adventure through one of the most artistic cultures in the world, where we will visit great art masterpieces, brilliant public architecture, artisan studios and workshops.

Explore with Peter de Kuster the power of the stories you tell yourself. With the concept of archetypal stories Peter explores with you the deep, unconscious patterns in the ways we perceive, organize, and interpret the events of our lives. A wide variety of these shared human themes are reflected in both our cultural traditions and stories and in our personal experiences the stories we live.

Discover the archetypal patterns and themes that influence your daily life with this new journey with Peter de Kuster . We will explore through a journey across some famous artists and their works the relative influence of such archetypes as Seeker, Warrior, Creator, Sage, Jester, Magician, Lover, and more in your own life. Using Peter’s stories and his ‘What Story are You Living’ instrument together, you will learn your strengths, challenges, growth opportunities, and strategies for self-improvement.

Awaken your unrealized potential and hidden strengths to improve personal and business relationships, find new direction in career planning, or replace unproductive life patterns. Understanding your life story and the decisions you make along the way will help you on the path to a fuller, more satisfying journey. Since the What Story are You Living journey is intended to help guide and improve your journey through life.

HOW AND WHY WE LIVE STORIES

We are storytelling creatures. Listen to people talking in a restaurant, at the water cooler or at a party and you will quickly find that the majority of what they say is in the form of stories. We connect by telling each other stories. We can better understand ourselves by recognizing and exploring our life narratives. Your life story is the tale that your repeatedly tell yourself about who you are, what you want, what you can and cannot do. Before the second year of life, we are sensitive to the tone of stories lived around us, and we have already begun collecting thousands of images that resonate emotionally with us in some important way. At first the plots are inconsistent and illogical – much as our dreams continue to be. By elementary school , we follow particular rules about the beginning, middle and ending of stories, so they begin to make sense. By adolescence, we tell ourselves consistent stories about our lives that define who we are, how we came to be that way, and where we are headed. We see events that we can recount as vignettes of our central life narrative.

Although there are as many variations of life stories as there are individuals, people tend to crete narratives according to a finite number of templates. There are a very small number of general narrative forms in the world’s literature, movies, art. The same is true of characters and the roles they play. How can this be?

In the first part of the twentieth century, the psychiatrist Carl Jung recognized the universality of characters and situations. Just as there are certain musical tones that sound resonant across cultures, there are similarly a universal set of roles, situations and themes that are recognizable by everyone. These universal templates are called archetypes, which is derived from the Greek archetypos, meaning ‘molded first as a model’ (Merriam Webster 2002). Jung, and many other after him, saw that these stories which recur in literature and art are the same narratives we as humans live. For example we all recognize the love story whether we encounter it in a movie, an opera , or a novel. And when we fall in love, we experience for ourselves what that story is about. When we are in a loving relationship, we not only learn major life lessons (in this case about intimacy, sensuality, pleasure, and commitment) but we also feel a sense of connection to all the other people who have ever loved deeply. While each love is different, there is a deep pattern that transcends these differences. When we understand the stories and recognize their universality, we can connect with each other at deeper and more conscious levels, using the archetypal stories as the foundation.

This may be especially true of the sacred myths of cultures, which are particularly archetypal, as they express in metaphor people’s actual experiences. These stories do not necessarily have to be taken literally. Rather, the concrete outward actions symbolize inner experiences. We read the story of an outward journey and something resonates in our inward journey.

This is why people talk about ‘life journeys’, even if they have never outwardly left the town where they grew up. People connect immediately to a journey story from another culture finding resonance with the characters and the form and the phases of the journey, even if the particular details are not familiar. Such stories influence people for good or ill. Archetypal stories can provide breakthroughs in insight and move people toward harmony and success, but such stories are equally able to tempt people toward less productive, even destructive behaviors. Either way, an understanding of the archetypal narrative can enhance insight or enable people to break free of destructive patterns.

The archetypal stories described in this seminar are those associated with the heroine’s journey, which is a model for the individuation process (the process of finding yourself and connecting to your depth and your full potential). They are named by the primary character in each story: Dreamer, Independent, Warrior, Caregiver, Explorer, Lover, Outlaw, Creator, Master, Magician, Sage and Jester.

Living the Stories in Everyday Life: Stages and Situations

When we are living a particular story, we tend to see the world from its vantage point. What we notice in the world and what actions we think make sense grow naturally from that story. For example when someone who is living a Warrior story is having a difficult time with another person she may react in a strong and challenging way, defending her own position. If this person were living a Caregiver story, however, she might instead show concern for what was causing the other person to be difficult, seeking to understand and reassure. When we develop narrative intelligence, we are able to see why we react the way we do and understand the different assumptions and behaviors of others.

There are a host of characters and situations from which these stories are drawn. Such characters have come to be known as archetypes, and they define basic stories, although for each person the details will be unique. These archetypes can be looked at as guides that help us know when we are on our best path and taking the most appropriate action. Your results from the Heroine’s Journey questionnaire help you identify these characters as a way to make sense out of the stories you are living, which allows you to create a richer and more satisfying life.

Many people recognize over time that there is one story that provides the central meaning and purpose of their lives. In addition, other stories are lived out at different times and places. If you think about it, you may notice that different stages of life have offered you new situations, new scenery, new people to be with, even the unfolding of a new storyline. You can see such situations as a stage set, with costumes and supporting characters that seem to pull you into a story line (the plot to be lived out). Such settings have immense power.

Certain life stages typically place us in situations that invite us into specific narratives. For example: if you had a very happy childhood, you likely lived the story of the Dreamer (Innocence). Others were caring for you, and you simply had to trust their wisdom, experiment, and learn what to do to succeed. Living this story provided you with a baseline sense of trust and optimism about life. Living this story provided you with a baseline sense of trust and optimism about life. If, on the other hand, your childhood was difficult you may have lived an Orphan story. This does not mean that you were literally orphaned (although it could). Rather it means that the adults in your life were too distracted, unskilled or wounded to care for you properly (physically, emotionally or intellectually). In this case, you may have experienced a story that had as theme the challenge of coping in a situation of minor or major deprivation or wounding. Likely this would provide a baseline approach to life that was more cautious and realistic, even pessimistic. Or you might have lived both stories – either sequentially (if your life situation changed) or the same time (if your experience with the caregivers in your life was mixed).

As you grew older; you may have become less dependent upon your parents and other authority figures, wanting to explore your own identity and the world outside. You might even have become somewhat oppositional, especially in your adolescent years. You might think of this as living an Explorer story; which exemplifies the gifts of independence and identiy. At roughly this same time in life, you may have become interested in romance; and so you began living out a Lovers’ story; developing the gifts of intimacy and sensuality. This may have led to marriage and children in which case you suddenly needed to live the story of the Caregiver, demonstrating the ability to nurture and even sacrifice for others.

The list of stories we may live at different stages of our lives can go on and on. The major point here is that success in life is often determined by how well we live out these stories, for it is in the living thtat we develop in mature, responsible, moral and successful adults.

So many people today talk about the need for character – in public officials, in the heads of corporations, and in the young. However character cannot be formed by simply enjoining people to act appropiately. We all know from making New Year’s resolutions that simply deciding to do or not do something is not enough to guarantee success. Becoming good, moral and successful requires knowledge of how to develop the inner qualities that make it easy to do so. Every life situation carries within it a call to live a story that offers experiences that can make us great – or, conversely, bring out what is petty, small or harmful within us. It is much easier to avoid the slippery slope of life’s negative temptations and traps when we can recognize the positive potential within situations.

The stories identified in this seminar link everyday life twith the great, mythic stories that inform what it means to be human. Many people, however, sleepwalk through stories that emerge naturally in certain life stages and life situations and consequently they lack a sense of meaning and purpose in their lives. At worst, living in this unconscious way decreases their ability to gain the gifts associated from living the great stories; leaves them feeling alone with their problems, and decreases their ability to become the kind of mature and wise people capable of making a positive difference to their families, friends, community and field of work. When people lack the ability to know what story they are living, they may fail to develop the qualities required to take adult responsibility for the state of their families, communities and the larger world.

When we recognize that we are living a unique personal story, as well as one of the universal great narratives , our lives can be filled with meaning, purpose and dignity. At the same time, we feel less lonely because we can see that we share commonality with all the people in all times and places, who have lived through the challenges of that story.

Exploring Archetypal Stories

Archetypes are psychological structures reflected in symbols, images and themes common to all cultures and all times. You see them in recurring images in art, literature, myths and dreams. You may experience archetypes directly as different parts of you. If you say that on one hand you want one thing and on the other you want something else, you can give archetypal names to those parts, as they generally communicate desires and motivations common to humans everywhere. Although the potential characters within us are universal, each of us expresses them differently, endowing them with somewhat different styles, traits and mannerisms. For example, when the Warrior is an archetype, different kinds of Warriors engage in difficult battles.

The Warrior Archetype encompasses the warlord and the samurai but it also might include the dedicated biologist racing to be on the first team to map the human genome, the advocate for social justice or the member of a street gang. Each of these Warriors follows a different code of honor, goals, style of dress etc; nevertheless all of them are Warriors. The expression of an archetype will be influenced by a person’s culture, setting and time in history but it will also be a manifestation of his or her individuality.

As aspects of yourself archetypes can reveal your most important desires and goals. Understanding their expression in your personal myths and stories helps you gain access to unrealized potential, grasp the logic and importance of your life and increase your empathy for the stories that others live.

In this computer-literate society you might think of an archetype as analogous to computer software that helps you to accomplish certain tasks. For example, a word processing program can be used to write a letter report or book; other applications help with accounting and financial planning and reporting. But these programs would be of no help if you confused their functions. Similarly, the Warrior helps people to be more focused, disciplined, and tough; the Lover helps them to be more passionate, intimate and loving; while the Jester helps them lighten up and enjoy their lives. When a particular archetype is awakened you live out its story. In the process you are able to accomplish definable new tasks. However it is also important that the archetype to be relevant to the task you are facing. If you are going on a date, the evening is not likely to end well if you act out a war story. Conversely most people find it wise not to go into war with the Lover’s vulnerability or the Jester’s playfulness.

In the ancient world, many people projected the archetypes outwardly onto images of gods and goddesses. In the twentieth century, Jung explored the manifestation of the psychological symbols of archetypes and their role in healing. The Hero’s Journey What Story are You Living? makes it easier for you to determine and recognize twelve of the archetypes in your daily life. Understanding your story and archetypes can help you better decide the underlying logic of your life, find greater fulfillment and satisfaction, and free yourself from living out limiting patterns and behaviors. Such knowledge can also increase your insight into other people, thus greatly enhancing your relationships. Most important, understanding these deep psychological structures will make your individuation process – the process of finding yourself and fulfilling your potential- conscious, so that you can gain the gifts associated with maturity, success and happiness.

When each archetype is active in a person’s life, it tends to call forth a particular kind of story or plot. After you have answered the Hero’s Journey What Story are You Living? questionnaire, you will want to become familiar with these stories and plots and their archetypal characters. After you have become familiar with the archetypes, you will want to validate and review your results and then develop some practical understanding of how to use this information by doing the exercises in this journey.

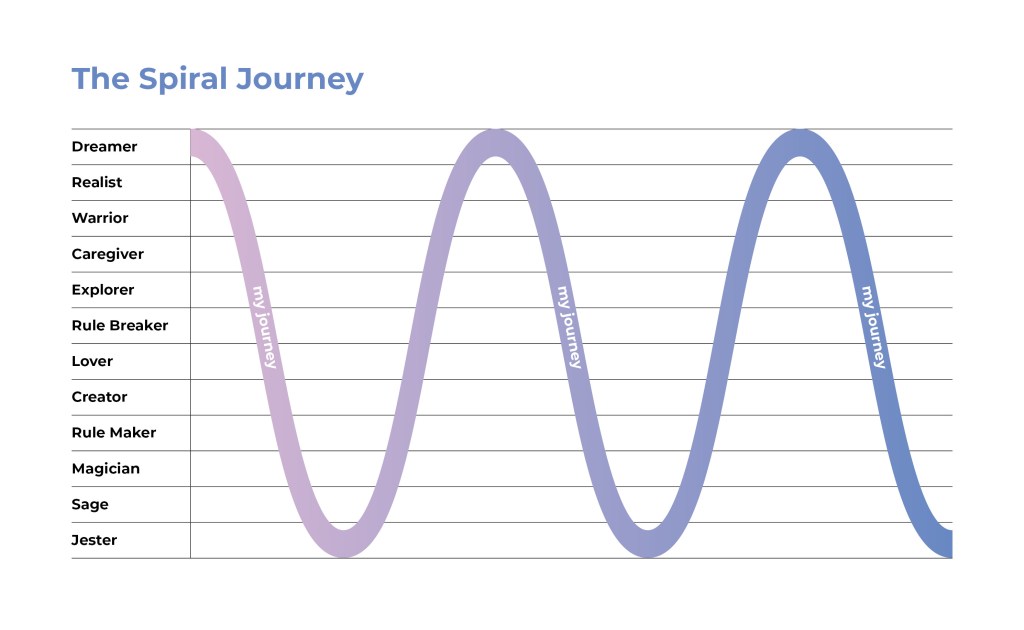

Archetypal Stages of the Journey

The archetypes and their stories are engaged more subtly as they emerge at different stages of the journey. The mythic hero’s journey is outlined in the picture beneath, however, it may or may not be the order in which you have lived the stories of these archetypes. The order in which the archetypes are presented is only a typical order in which they may be encountered during the course of development and thus a logical order in the unfolding of a story. In addition, one or more archetypes may be active throughout your life and become critical to your sense of who you are. To begin your understanding of how archetypes influence your life review the summary of archetypes above and check the archetypes that are most germane to your life at this time.

Citizen Kane

Charles Foster Kane’s journey in Citizen Kane is a profound meditation on the spiral nature of the hero’s journey-a pattern not of linear conquest, but of recurring archetypes, unresolved wounds, and ever-deepening cycles of self-discovery and loss. In this analysis, we’ll walk through the 12 classic archetypes of the hero’s journey as they appear in Kane’s life, illustrating how the spiral repeats and deepens, and inviting you to reflect on your own story. Along the way, you’ll find questions and exercises to help you become the storyteller of your own legend.

1. The Ordinary World: Innocence and Loss

Kane’s journey begins in the snowy wilderness of Colorado, a child playing with his sled, Rosebud. This is his “ordinary world”-a place of innocence, security, and familial love. But even here, the seeds of loss are planted: his mother, Mary Kane, is emotionally distant, and his father is powerless. The discovery of gold changes everything, and Kane’s world is shattered when he’s sent away to live with Thatcher, the banker.

Reflect:

- What was your “ordinary world” as a child?

- What moments or decisions changed that world forever?

Exercise:

Write a short scene describing a time when your sense of safety or innocence was disrupted. What did you lose? What did you gain?

2. The Call to Adventure: The Promise of Power

Kane’s call to adventure is not a choice, but a command: he is taken from his parents and thrust into a new world of wealth and privilege. Later, as a young man, he inherits a vast fortune and chooses to run the Inquirer, launching himself into public life. The adventure promises power, influence, and the chance to shape the world.

Reflect:

- When have you been called (or forced) to leave your comfort zone?

- Did you embrace or resist the call?

Exercise:

List three moments in your life when you were presented with a new opportunity or challenge. Did you accept or decline? Why?

3. Refusal of the Call: Clinging to the Past

Kane resists his new destiny. As a boy, he clings to his sled, fighting Thatcher’s authority. As an adult, he insists he’s acting for the people, not for power. Yet, beneath the bravado, he is haunted by the loss of his childhood and the love he never received.

Reflect:

- Have you ever resisted change, even when it was inevitable?

- What were you afraid of losing?

Exercise:

Write about a time you refused a challenge or opportunity. What held you back? What did you fear?

4. Meeting the Mentor: Guidance and Rejection

Kane’s mentors are complex and often unsatisfying. Thatcher, his guardian, offers financial wisdom but no warmth. Jedediah Leland, his friend, tries to guide Kane toward integrity. Even Susan, his second wife, attempts to nurture him. Yet Kane repeatedly rejects or outgrows his mentors, unable to accept the love or guidance he truly needs.

Reflect:

- Who have been your mentors? Did you accept their help?

- What kind of guidance do you seek now?

Exercise:

Identify a mentor figure in your life. Write a letter (real or imaginary) thanking them or expressing what you wish you could have received from them.

5. Crossing the Threshold: The World of Power

Kane’s commitment to running the Inquirer marks his crossing into the world of influence and ambition. He leaves behind the possibility of a simple life, embracing the complexities of public scrutiny, political ambition, and personal rivalry.

Reflect:

- When have you crossed a threshold, leaving behind the familiar for the unknown?

- How did it change you?

Exercise:

Describe a moment when you made a decision that changed the course of your life. What did you leave behind? What did you step into?

6. Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The Battle for Identity

As Kane’s power grows, so do his challenges. He faces tests (political campaigns, business rivalries), gains allies (Leland, Bernstein), and makes enemies (Thatcher, Gettys). His relationships are fraught with tension-he demands loyalty but gives little in return, driving away those who care for him.

Reflect:

- Who are your allies and adversaries?

- What tests have shaped your character?

Exercise:

Draw a map of your life’s “allies and enemies.” Who has helped you? Who has challenged you? What have you learned from each?

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave: Loneliness and Confrontation

Kane’s spiral deepens as he faces the collapse of his marriage, the failure of his political ambitions, and the death of his dreams. He retreats to Xanadu, his vast, empty estate-a literal and metaphorical “inmost cave.” Here, surrounded by wealth but isolated from love, Kane confronts the emptiness at the heart of his quest.

Reflect:

- What is your “inmost cave”-the place where you face your deepest fears?

- What have you found there?

Exercise:

Write about a time you withdrew from the world. What were you seeking? What did you discover about yourself?

8. The Ordeal: The Dark Night of the Soul

Kane’s greatest ordeal comes when Susan leaves him. His desperate plea for her to stay reveals his core wound: the fear of abandonment and the inability to love or be loved unconditionally. In his rage, he destroys her room, but the real destruction is internal-a shattering of hope and self-worth.

Reflect:

- What has been your greatest ordeal?

- How did it change you?

Exercise:

Recall a moment of deep crisis. Write a dialogue between your present self and your past self at that moment. What would you say to comfort or guide yourself?

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword): The Hollow Victory

Unlike traditional heroes, Kane’s “reward” is ambiguous. He retains his wealth and notoriety but loses the people who mattered. The empty halls of Xanadu and his obsessive collecting reveal the hollowness of his victories-he has everything, yet nothing.

Reflect:

- Have you ever achieved a goal only to find it unfulfilling?

- What did you truly want?

Exercise:

List three “rewards” you’ve pursued. Did they bring you happiness? If not, what was missing?

10. The Road Back: Nostalgia and Regret

After Susan’s departure, Kane is left with memories and regret. He revisits the past, longing for the simplicity of childhood. The spiral brings him back to the beginning: alone, misunderstood, and yearning for something he cannot name. The road back is not triumphant but haunted by nostalgia.

Reflect:

- Do you revisit the past, searching for meaning or closure?

- What memories do you return to, and why?

Exercise:

Write about a memory you often revisit. What draws you back? What are you seeking?

11. Resurrection: The Final Reckoning

Kane’s final days are spent wandering Xanadu, surrounded by the detritus of his life. In death, he is resurrected in memory, as reporters and acquaintances try to piece together his story. “Rosebud,” his dying word, is a return to the innocence and loss that defined his journey-a resurrection of the child he once was.

Reflect:

- How do you want to be remembered?

- What part of your story do you hope will endure?

Exercise:

Imagine your life as a movie. What would your final scene be? What message would you want to leave behind?

12. Return with the Elixir: The Gift of Understanding

The “elixir” Kane brings back is not for himself, but for the audience. The search for Rosebud is a quest for meaning, and its answer-a simple sled-reminds us that what we seek is often what we lost long ago. Kane’s story, told through the spiral of memory and regret, offers a cautionary tale about the cost of ambition and the enduring need for love.

Reflect:

- What wisdom have you gained from your journey?

- What gift can you offer to others from your experience?

Exercise:

Write a letter to your younger self, sharing the most important lesson you’ve learned. What advice or comfort would you give?

The Spiral Nature of Kane’s Journey

Unlike a linear path, Kane’s hero’s journey is a spiral. Each archetype reappears at different stages and depths, colored by new experiences and old wounds. His longing for love, his quest for power, his resistance to vulnerability-all recur, each time with greater stakes and more profound consequences.

Kane as Archetype:

- The Innocent Child: Kane’s longing for love and security is never resolved, haunting him throughout his life

- The Seeker: His pursuit of power and influence is a search for meaning, but it only deepens his isolation.

- The Ruler: As master of Xanadu, Kane is at the height of his power but also at his most powerless to change his fate.

- The Outcast: In the end, Kane is a stranger to everyone, including himself, spiraling back to the loneliness of his childhood.

Character Analysis:

- Charles Foster Kane: A tragic hero, driven by unresolved childhood trauma, seeking love and control but unable to find fulfillment.

- Jedediah Leland: The loyal friend and would-be mentor, representing integrity and the voice of conscience.

- Susan Alexander: The second wife, both muse and victim, whose departure marks Kane’s final defeat.

- Walter Parks Thatcher: The mentor-guardian, offering security but no warmth, shaping Kane’s distrust of authority.

- Mary Kane: The distant mother, whose decision to send Kane away sets the spiral in motion.

Your Story: Becoming the Storyteller of Your Own Life

Kane’s journey is a cautionary tale, but it is also an invitation. You are the storyteller of your own life. You can choose to repeat old patterns or create new legends. The spiral of the hero’s journey is not a trap, but a path-one that you can walk with awareness, courage, and creativity.

Questions for Your Journey:

- What is the “Rosebud” in your life-the lost innocence or longing that shapes your choices?

- Are you living someone else’s story, or writing your own?

- What archetype are you embodying right now? What archetype is calling you next?

Exercises for Your Legend:

- The Story Map:

Draw a spiral on a piece of paper. Mark the key events of your life along the spiral, noting which archetype you were living at each point. Where do you see patterns repeating? Where have you grown? - The Character Interview:

Choose a character from your life (yourself, a mentor, an adversary). Write an interview with them. What do they want? What do they fear? How have they helped or hindered your journey? - The Rewrite:

Pick a moment in your life when you felt stuck or defeated. Rewrite the scene as if you were the hero, making a different choice. How does the story change? What new possibilities emerge? - The Legend Statement:

Write a one-sentence legend for your life. (“I am the one who…”) How does this legend empower or limit you? What new legend do you want to create?

Conclusion: Creating Your Own Legend

Citizen Kane is more than a film; it is a mirror held up to our own lives. Kane’s spiral journey through the 12 archetypes is a reminder that we are all searching for meaning, love, and belonging. We all face moments of loss, resistance, triumph, and regret. But unlike Kane, we have the power to become conscious storytellers-to revisit old wounds with new wisdom, to choose different paths, to create legends that heal and inspire.

As you reflect on Kane’s journey, ask yourself:

What story are you living? What story do you want to tell? Will you let the past define you, or will you become the hero of your own legend?

Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind is a sweeping epic of love, war, and survival, but beneath its grand historical drama lies a deeply personal hero’s journey-one that spirals through the 12 archetypes, not as a straightforward ascent, but as a cycle of triumphs, failures, and self-reinvention. Scarlett O’Hara, the story’s central figure, is no traditional hero. She is flawed, complex, and often her own worst enemy, yet her journey through the collapse and rebirth of the South is a powerful lens for exploring the spiral nature of the hero’s journey and the archetypes that shape every life-including yours.

Below, you’ll find a detailed exploration of the hero’s journey in Gone with the Wind, illustrated through Scarlett’s story and the supporting cast, with reflection questions and exercises to help you map your own legend.

The Spiral Hero’s Journey in Gone with the Wind

1. Ordinary World: The Innocent, Everyman, and Ruler

Scarlett’s journey begins on Tara, her family’s plantation, where she is the pampered belle of the county. She is the Innocent-protected, naïve, and confident in her charms. She is also the Ruler, presiding over her social world, and the Everyman, shaped by the expectations and routines of Southern womanhood96.

Reflection:

Where is your “ordinary world”? What roles do you play-Innocent, Ruler, Everyman? What do you take for granted?

Exercise:

Describe your own “Tara”-the place, community, or routine where you feel most secure. What strengths and blind spots does this world give you?

2. Call to Adventure: The Herald and Explorer

Scarlett’s call to adventure comes with the outbreak of the Civil War and the shattering of her world. The Herald is both the war itself and the loss of Ashley Wilkes, whom she loves but cannot have. Forced to confront a world in chaos, Scarlett is thrust into the role of Explorer, seeking new ways to survive and thrive.

Reflection:

What event or realization has called you out of your comfort zone? Who or what is your Herald?

Exercise:

List three moments when you were forced to adapt or change. How did you respond? Did you resist or embrace the adventure?

3. Refusal of the Call: The Doubter and Orphan

Scarlett’s initial response is denial. She clings to the hope of winning Ashley and resists the reality of war, loss, and change. She is the Doubter, refusing to accept the new world, and the Orphan, soon to be stripped of her family, home, and innocence.

Reflection:

When have you resisted change, hoping things would return to “normal”? What did you fear losing?

Exercise:

Write about a time you refused a call to adventure. What was at stake? What finally pushed you to act?

4. Meeting the Mentor: The Sage, Caregiver, and Shadow

Scarlett’s mentors are complex and often contradictory. Mammy, her family’s housekeeper, is a true Sage and Caregiver, offering wisdom and moral grounding. Rhett Butler, the charismatic anti-hero, is both Mentor and Shadow-challenging Scarlett, exposing her flaws, and urging her to face uncomfortable truths. Melanie Hamilton, too, is a moral mentor, embodying kindness and resilience.

Reflection:

Who are your mentors? Are they always positive influences, or do they challenge you in uncomfortable ways?

Exercise:

Write a letter to a mentor (real or imagined). What have you learned from them? How did their guidance shape your journey?

5. Crossing the First Threshold: The Shapeshifter and Trickster

Scarlett crosses the threshold when Atlanta falls and she must flee, taking responsibility for Melanie and her newborn child. She becomes a Shapeshifter, adapting to each crisis, and a Trickster, using wit and deception to survive-lying, scheming, and even marrying for security.

Reflection:

When have you been forced to adapt quickly, taking on new roles or disguises to survive?

Exercise:

Describe a time you became a Shapeshifter or Trickster-bending the rules, changing your persona, or using cunning to get by.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies: The Ally, Shadow, and Ruler

Scarlett’s journey is filled with tests:

- Surviving the burning of Atlanta

- Returning to Tara and finding it devastated

- Taking charge of her family’s survival

Her allies include Mammy, Melanie, and (sometimes) Rhett. Her enemies are poverty, hunger, and the changing social order. She is her own Ruler, but also faces external Rulers-Yankee occupiers, carpetbaggers, and the rigid codes of Southern society.

Reflection:

Who are your allies and enemies? What tests have shaped your journey?

Exercise:

Map your “cast of characters.” Who helps you? Who hinders you? Who rules over your choices?

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave: The Orphan, Martyr, and Creator

Scarlett’s “inmost cave” is Tara itself-her home, her identity, and her greatest vulnerability. She becomes the Orphan, stripped of her parents and security; the Martyr, sacrificing her pride and morals to save her family; and the Creator, rebuilding Tara and later her own business empire98.

Reflection:

What is your “inmost cave”-the place or challenge that holds your deepest fears and hopes?

Exercise:

Write about a time you had to sacrifice or reinvent yourself to protect what mattered most.

8. The Ordeal: The Shadow, Martyr, and Lover

Scarlett’s ordeal is ongoing:

- She marries Frank Kennedy for money, sacrificing love for survival

- She faces violence and attack in a lawless Atlanta

- She loses her daughter, Bonnie, and Melanie dies

The Shadow is both external (war, loss) and internal (her own selfishness and inability to love fully). The Martyr is seen in her sacrifices; the Lover in her obsession with Ashley and her tumultuous relationship with Rhett.

Reflection:

When have you faced your greatest ordeal? What shadows did you confront-inside and out?

Exercise:

Describe your own “ordeal”-a crisis that tested your values, relationships, or sense of self. What did you learn?

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword): The Ruler, Lover, and Sage

Scarlett’s reward is ambiguous. She gains wealth, security, and power-becoming the Ruler of her own destiny and the business world. She marries Rhett, believing she has finally won. Yet, her inability to recognize real love (with Rhett) and her fixation on Ashley mean her “reward” is fraught with loss and regret. The Sage archetype is present in the hard lessons she learns about herself and others.

Reflection:

What rewards have you gained from your struggles? Were they what you truly wanted?

Exercise:

List three “swords” you’ve seized-achievements, relationships, or insights. How have they changed you?

10. The Road Back: The Hero, Martyr, and Shadow

Scarlett’s road back is marked by tragedy and realization. Bonnie’s death, Melanie’s passing, and Rhett’s departure force Scarlett to confront the emptiness of her victories. She is the Hero, surviving against all odds; the Martyr, suffering for her choices; and the Shadow, facing the consequences of her flaws.

Reflection:

When have you returned from a journey changed, but not in the way you expected? What did you lose-and what did you gain?

Exercise:

Write about a time you “came back” from a challenge, only to find the world-and yourself-irrevocably changed.

11. Resurrection: The Magician, Orphan, and Sage

Scarlett’s resurrection is a moment of self-awareness. Alone at Tara, she vows to rebuild and win Rhett back. The Magician archetype is present in her ability to transform adversity into hope. She is the Orphan, once more alone, but now tempered by experience. The Sage emerges as she finally understands the nature of love, loss, and survival.

Reflection:

When have you experienced a resurrection-a moment of clarity or transformation after loss?

Exercise:

Imagine your own resurrection scene. What wisdom or power do you bring back from the depths?

12. Return with the Elixir: The Sage, Ruler, and Everyman

Scarlett’s journey ends where it began-at Tara. She is changed: wiser, sadder, but still unbroken. The “elixir” is her resilience and the hard-won knowledge that tomorrow is another day. She is the Sage, carrying wisdom; the Ruler, determined to shape her fate; and the Everyman, forever seeking belonging and love.

Reflection:

What “elixir” do you bring back from your journey? How are you changed? How do you share your gifts with others?

Exercise:

Write a letter to your future self, describing the strengths, lessons, or hopes you want to carry forward.

The Spiral Nature of Archetypes in Gone with the Wind

Archetypes in Gone with the Wind are not static-they spiral, reappear, and deepen as Scarlett’s journey unfolds. Here’s how the 12 archetypes recur:

| Archetype | Scarlett’s Story Example | Your Story Reflection |

|---|---|---|

| Innocent | Scarlett at Tara, before the war | Where do you find comfort or naivety? |

| Everyman | Her struggles for survival, blending in with society | When do you feel ordinary, yet called to greatness? |

| Orphan | After her parents’ deaths, left to rebuild | When have you felt abandoned or alone? |

| Explorer | Adapting to the new South, seeking opportunity | When have you ventured into the unknown? |

| Sage | Mammy, Rhett, Melanie, and Scarlett’s own hard-won wisdom | Who offers you guidance? What truths have you learned? |

| Caregiver | Mammy, Melanie, Scarlett for her family | Who do you nurture or protect? |

| Trickster | Scarlett’s schemes, Rhett’s provocations | Where do you use cunning or humor to survive? |

| Shapeshifter | Scarlett’s changing roles-belle, widow, businesswoman | When do you change masks or adapt to survive? |

| Shadow | War, poverty, her own selfishness, and obsession | What are your greatest obstacles? |

| Martyr | Sacrificing for Tara, marrying for money | When have you suffered for others or for survival? |

| Lover | Her passion for Ashley, tumult with Rhett | What or who do you love deeply? |

| Magician | Transforming adversity into hope, “Tomorrow is another day” | When have you experienced a profound change? |

| Ruler | Taking charge of Tara, her business, and her destiny | Where do you lead or wield power? |

Exercises: Exploring Your Own Hero’s Journey

- Draw Your Spiral:

Sketch a spiral and label each turn with an archetype you’ve encountered. Where do you see patterns repeating? Where have you grown? - Write Your Legend:

Begin your story: “Once upon a time, I…” Let the archetypes guide your narrative. Who are your allies? Your shadows? Your mentors? - Identify Your Ordeal:

What challenge has defined your journey so far? How did you face it? What archetypes helped or hindered you? - Claim Your Elixir:

What is the gift, insight, or strength you bring back to your world? How will you share it? - Ask Yourself:

- Where am I on my journey right now?

- What archetype do I embody most strongly?

- What legend am I creating-or avoiding?

You Are the Storyteller of Your Own Life

Gone with the Wind is not just the story of Scarlett O’Hara, but a mirror for every reader’s journey. The spiral of archetypes-Innocent, Ruler, Orphan, Shadow, Sage, and more-reminds us that heroism is not about perfection, but about resilience, adaptation, and the willingness to begin again. You are the storyteller. You can create your own legend, or let it be written for you.

“After all, tomorrow is another day.”

– Scarlett O’Hara

Will you answer your call to adventure? Will you spiral onward, learning, growing, and returning home transformed? The story is yours to tell.

Some Like It Hot

Some Like It Hot is a masterclass in the Hero’s Journey, not just for its comedic brilliance, but for how it spirals through the 12 classic archetypes, revealing how transformation, disguise, and self-discovery aren’t just for mythical heroes-they’re for all of us. As you read, reflect on your own journey: Where do you find yourself in the spiral? Which archetypes are calling you? What legend are you writing with your life?

The Hero’s Journey in Some Like It Hot: A Spiral of Archetypes

The Hero’s Journey is a cyclical path of transformation, marked by archetypal energies that appear, evolve, and recur as the hero grows8910. In Some Like It Hot, Joe and Jerry’s journey is both literal and metaphorical, as they run from danger, don disguises, and ultimately discover truths about themselves and love.

Let’s spiral through the 12 stages, illuminating the archetypes as they appear, reappear, and deepen-and invite you to reflect on your own story at each turn.

1. The Ordinary World: The Everyman and Trickster

Joe and Jerry are struggling jazz musicians in Prohibition-era Chicago, scraping by in a world of speakeasies and shady deals. They are Everymen-relatable, flawed, and just trying to survive. The Trickster energy is already present: Joe’s schemes and Jerry’s anxious improvisations hint at the chaos to come.

Reflection: Where is your “ordinary world”? What routines, roles, or disguises do you wear to get by?

Exercise: Write a snapshot of your daily life. Where do you play it safe? Where do you “bend the rules” to survive?

2. Call to Adventure: The Herald and Shadow

The inciting incident arrives violently: Joe and Jerry witness the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, making them targets of Spats Colombo’s gang-the Shadow archetype. The Call to Adventure is clear: run or die.

Reflection: What event or realization has forced you to change or escape? Who or what is your “Shadow”-the threat that pushes you out of comfort?

Exercise: List three moments when you were forced to act by circumstances beyond your control. What “shadow” drove you forward?

3. Refusal of the Call: The Doubter and Everyman

Initially, Joe and Jerry hesitate. They’re broke, scared, and unsure how to escape. Their reluctance is palpable-they are Doubters, clinging to the familiar even as danger closes in.

Reflection: When have you resisted change, even when you knew it was necessary?

Exercise: Describe a time you refused a call to adventure. What held you back? How did you finally move forward?

4. Meeting the Mentor: The Mentor and Ally

Mentorship in Some Like It Hot is unconventional. Sweet Sue, the bandleader, offers Joe and Jerry a lifeline (albeit unknowingly), while Sugar Kane becomes an emotional mentor, showing them vulnerability and trust. Even Osgood, with his unflagging optimism, models acceptance and joy.

Reflection: Who has mentored you, intentionally or not? What lessons did you learn from unexpected sources?

Exercise: Write a letter to an unlikely mentor in your life. What did you learn from them, even if they didn’t know they were teaching?

5. Crossing the First Threshold: The Shapeshifter and Threshold Guardian

Joe and Jerry cross a literal and figurative threshold when they disguise themselves as “Josephine” and “Daphne” to join Sweet Sue’s all-female band, boarding the train to Miami15. The Shapeshifter archetype is embodied in their new identities, while Sweet Sue and the band serve as Threshold Guardians, testing their ability to blend in.

Reflection: When have you had to change your identity or adapt to a new environment to survive or succeed?

Exercise: Describe a time you “crossed a threshold”-started a new job, moved, or entered a new community. What did you have to change about yourself?

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies: The Ally, Shadow, and Trickster

On the train and in Miami, Joe and Jerry face a series of tests: maintaining their disguises, resisting temptation, and navigating the affections of Sugar and Osgood. Sugar is an Ally, while Spats and his gang remain the looming Shadow. The Trickster energy is everywhere-Joe’s schemes, Jerry’s improvisations, and the film’s constant play with identity.

Reflection: Who are your allies and adversaries? Where do you encounter trickster energy-unexpected chaos or comic relief-in your life?

Exercise: Map your “band”-the people who travel with you through life. Who helps you? Who hinders you? Who keeps you laughing?

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave: The Lover and Creator

Joe, as “Junior,” woos Sugar on Osgood’s yacht, creating a new persona and risking exposure for love. Jerry, as “Daphne,” is courted by Osgood, experiencing affection and validation he never expected. The Lover archetype is awakened, and both men are forced to confront what they truly want.

Reflection: When have you risked everything for love, creativity, or authenticity? What “cave” did you approach, knowing you might be changed forever?

Exercise: Write about a time you created a new version of yourself for love or ambition. What did you discover in the process?

8. The Ordeal: The Shadow and Martyr

The mobsters arrive in Miami for a national conference, and Joe and Jerry are recognized as witnesses to the massacre. The Shadow is at its most dangerous. The Ordeal is a matter of life and death-can they escape, or will their disguises fail?

Reflection: What has been your greatest ordeal? When have you faced your Shadow directly, risking everything?

Exercise: Describe your own “ordeal”-a crisis that forced you to confront your deepest fears. What did you sacrifice? What did you gain?

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword): The Sage and Shapeshifter

After surviving the mob’s wrath, Joe and Jerry seize the “reward”: a chance at real love and freedom15. Joe reveals his true self to Sugar, risking rejection but gaining authenticity. Jerry, as Daphne, is offered unconditional acceptance by Osgood, challenging his assumptions about love and identity.

Reflection: What rewards have you gained by being honest or vulnerable? When has dropping your mask brought unexpected gifts?

Exercise: List three “swords” you’ve seized-moments when you claimed your truth, even if it was risky.

10. The Road Back: The Hero and Ally

Joe and Jerry must escape the hotel as Spats’ men pursue them. The Hero archetype is fully awakened-they take action not just for themselves, but for those they care about. Allies rally: Sugar helps Joe, Osgood helps Jerry.

Reflection: When have you returned from a crisis with new strength or purpose? Who helped you on the road back?

Exercise: Write about a time you “came back” from the brink. How did you use what you learned to help others?

11. Resurrection: The Magician and Ruler

The climax is a comic resurrection: Joe and Jerry shed their disguises and face the world as their true selves. Joe is transformed by love; Jerry, by acceptance. The Magician archetype is present in the film’s final moments-transformation, revelation, and the magic of being “seen.” Osgood, the Ruler, offers Jerry a new kind of belonging.

Reflection: When have you been “resurrected” by love, truth, or acceptance? What magic changed you?

Exercise: Imagine your own resurrection scene. What mask would you drop? Who would accept you, “flaws” and all?

12. Return with the Elixir: The Lover, Sage, and Everyman

Joe and Jerry return to the world, changed. Joe is united with Sugar, who accepts him despite his deception. Jerry, in the film’s iconic final line, is accepted by Osgood: “Nobody’s perfect!”. The elixir is self-acceptance, love, and the wisdom that comes from embracing imperfection.

Reflection: What “elixir” do you bring back from your journey? How are you changed? How do you share your gifts with others?

Exercise: Write a letter to your future self, describing the gifts-wisdom, love, acceptance-you hope to carry forward.

The Spiral Nature of the 12 Archetypes in Some Like It Hot

Archetypes in Some Like It Hot aren’t static-they spiral, reappear, and deepen as the story unfolds. Here’s how they map onto the characters and story beats:

| Archetype | Example in Film | Your Story Reflection |

|---|---|---|

| Hero | Joe and Jerry risking everything to survive and love | When have you acted bravely in the face of danger? |

| Mentor | Sweet Sue, Sugar, Osgood’s acceptance | Who has guided you, knowingly or not? |

| Threshold Guardian | Sweet Sue, the band, the mobsters | What obstacles test your resolve? |

| Herald | The massacre, the mob threat | What calls you to adventure or change? |

| Shapeshifter | Joe and Jerry’s disguises, shifting identities | When have you changed roles or masks? |

| Shadow | Spats Colombo and the mob | What are your greatest fears or threats? |

| Ally | Sugar, Osgood, each other | Who stands by you, even in disguise? |

| Trickster | Joe’s schemes, Jerry’s improvisations | Where does humor or chaos help you adapt? |

| Lover | Sugar, Osgood, romantic longing | What do you love enough to risk everything for? |

| Creator | Joe’s “Junior” persona, Jerry’s Daphne | What new self have you created? |

| Ruler | Osgood’s acceptance, Sweet Sue’s leadership | Where do you lead or create safe spaces? |

| Sage | Wisdom gained through risk and revelation | What lessons have you learned from your journey? |

Exercises: Exploring Your Own Hero’s Journey

- Draw Your Spiral: Sketch a spiral and label each turn with an archetype you’ve encountered. Where do you see patterns repeating? Where have you grown?

- Write Your Legend: Start your story: “Once upon a time, I…” Let the archetypes guide your narrative. Who are your allies? Your shadows? Your mentors?

- Identify Your Ordeal: What challenge has defined your journey so far? How did you face it? What archetypes helped or hindered you?

- Claim Your Elixir: What is the gift, insight, or strength you bring back to your world? How will you share it?

- Ask Yourself:

- Where am I on my journey?

- What archetype do I embody now?

- What legend am I creating-or avoiding?

You Are the Storyteller of Your Own Life

Some Like It Hot reminds us that heroism isn’t always about swords and dragons. Sometimes it’s about survival, disguise, improvisation, and the courage to reveal your true self, even when “nobody’s perfect.” The 12 archetypes-Hero, Mentor, Shadow, Trickster, Lover, and more-are not just characters in a story, but living energies in your own life, spiraling through each challenge and triumph.

You are the storyteller. You can create your own legend-or let others write it for you.

“Well, nobody’s perfect.”

- Osgood Fielding III, Some Like It Hot

Will you answer your call to adventure? Will you spiral onward, learning, growing, and returning home transformed? The story is yours to tell.

Robin Hood

The hero’s journey is not just a formula-it’s a living spiral, a map for transformation that echoes through the greatest legends and the quietest moments of our lives. In The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938, starring Errol Flynn), this journey unfolds with vibrant clarity, each archetype circling back in new forms as Robin, outlaw and hero, rises to meet injustice and claim his legend.

But this spiral is not reserved for Robin alone. As you read, consider: How do these archetypes appear in your own story? Where are you on your journey? What legend are you creating-or will you let your story be written by others?

The Spiral of the Hero’s Journey in The Adventures of Robin Hood

The hero’s journey, or monomyth, is classically divided into 12 stages, each marked by the appearance of archetypes-universal characters or energies that guide, challenge, and transform the hero8910. In Robin Hood, these archetypes don’t appear just once; they spiral through the story, revisited at deeper levels as Robin grows. Let’s follow Robin’s path, and see how the 12 archetypes spiral through his adventure-and yours.

1. The Ordinary World: The Hero and Everyman

Robin of Locksley begins as a nobleman in a divided England, living under the shadow of Prince John’s tyranny. He’s both the Hero-brave, skilled, and principled-and the Everyman, rooted in his community, grounded in simple values.

Reflection: Where is your “ordinary world”? What values or routines define your starting point?

Exercise: Write a paragraph describing your own “Sherwood”-the place or state where your journey begins. What do you take for granted? What feels safe or stifling?

2. Call to Adventure: The Herald and Rebel

The call comes when Robin witnesses the execution of Much the Miller’s Son for poaching. Outraged, Robin saves Much, openly defies Prince John, and is declared an outlaw. The Herald archetype (the event that calls the hero to action) and the Rebel (the urge to challenge injustice) spiral together here.

Reflection: What has called you to step beyond your comfort zone?

Exercise: List three moments in your life when you felt compelled to challenge the status quo. What “herald” delivered the message?

3. Refusal of the Call: The Doubter and Everyman

Robin’s refusal is brief but real-he could flee, hide, or submit. Instead, he chooses the harder path of resistance. The Everyman’s fear and the Doubter’s uncertainty spiral through this moment.

Reflection: When have you hesitated to answer a call? What held you back?

Exercise: Write about a time you “refused the call.” What did you fear losing? What did you fear discovering?

4. Meeting the Mentor: The Mentor and Sage

Robin’s mentors are many: King Richard’s example, Friar Tuck’s wisdom, and even Marian’s moral clarity. The Mentor archetype provides guidance, encouragement, and sometimes a “magical” gift-like Friar Tuck’s sword or Marian’s information.

Reflection: Who has guided you in times of uncertainty?

Exercise: Write a letter to a mentor (real or imagined). What wisdom did they offer? How did it shape your journey?

5. Crossing the Threshold: The Threshold Guardian and Ally

Robin crosses into Sherwood Forest, leaving behind his old life. Here, he meets allies-Much, Will Scarlet, Little John-who test and welcome him. The Threshold Guardian (the challenge at the boundary) and the Ally archetypes spiral together.

Reflection: What “threshold” have you crossed? Who helped or hindered you?

Exercise: Draw a map of your journey so far. Mark the thresholds you’ve crossed and the allies you’ve gained.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies: The Trickster, Ally, and Shadow

Robin’s band faces many tests: stealing from the rich, outwitting the Sheriff, recruiting Friar Tuck, and surviving ambushes. The Trickster (Robin’s wit), the Ally (his band), and the Shadow (Prince John, Gisbourne, the Sheriff) all spiral through these trials1510.

Reflection: Who are your allies and adversaries? How do they test or teach you?

Exercise: Make a list of the “characters” in your life. Assign them archetypes: Ally, Shadow, Trickster, etc. How do they shape your journey?

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave: The Lover and Creator

The “inmost cave” is both literal and symbolic. Robin approaches Marian, risking vulnerability. He also plans the rescue of King Richard-a creative, daring scheme. The Lover and Creator archetypes spiral together, as love and ingenuity fuel his courage.

Reflection: What risks have you taken for love or creativity?

Exercise: Write about a time you approached your own “inmost cave”-a challenge that required both heart and invention.

8. The Ordeal: The Shadow and Martyr

The archery tournament is a trap. Robin is captured, faces death, and must rely on his friends and Marian’s courage to survive. The Shadow (Gisbourne, Prince John) and the Martyr (Robin’s willingness to sacrifice) spiral through this ordeal.

Reflection: What has been your greatest ordeal? Who or what was your “shadow”?

Exercise: Describe your own “archery tournament”-a moment when you risked everything. What did you learn?

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword): The Sage and Ruler

Robin escapes, his legend grows, and he gains new wisdom-about leadership, loyalty, and love. The Sage (hard-won wisdom) and the Ruler (emerging leadership) spiral through this reward.

Reflection: What rewards have you gained from hardship?

Exercise: List three “swords” you’ve seized-skills, insights, or relationships earned through struggle.

10. The Road Back: The Hero and Ally

Robin must act quickly to save Marian and King Richard. The Hero returns, now stronger, and his allies rally for the final battle. The spiral brings old archetypes-Hero, Ally-back in new forms15.

Reflection: When have you returned to face an old challenge, changed by your journey?

Exercise: Write about a time you “came back” to something difficult. How were you different?

11. Resurrection: The Magician and Ruler

The climax: Robin and Richard, disguised as monks, infiltrate Nottingham Castle. Robin’s cleverness (Magician) and his leadership (Ruler) spiral together as he defeats Gisbourne, frees Marian, and restores the king.

Reflection: What has resurrected you after defeat? What new power or insight emerged?

Exercise: Imagine your own “castle rescue.” What disguise or strategy would you use? Who would you save?

12. Return with the Elixir: The Lover, Everyman, and Sage

Robin is pardoned, his men are freed, and he is united with Marian. He returns not just as a hero, but as a wiser, more compassionate leader. The Lover, Everyman, and Sage archetypes spiral together, completing the circle.

Reflection: What “elixir” do you bring back to your world? How are you changed?

Exercise: Write a letter to your future self, describing the gifts you hope to carry forward from your journey.

The Spiral Nature of Archetypes in Robin Hood

Archetypes are not static; they spiral, reappear, and deepen as the story unfolds. In Robin Hood, each archetype is revisited at new levels:

| Archetype | Robin Hood Example | Your Story Reflection |

|---|---|---|

| Hero | Defying Prince John, leading the outlaws | When have you stood up for what’s right? |

| Mentor | Friar Tuck, King Richard, Marian’s wisdom | Who has guided you? |

| Threshold Guardian | Little John at the bridge, the Sheriff’s traps | What obstacles have tested your resolve? |

| Herald | News of Richard’s capture, Much’s plight | What has called you to adventure? |

| Shapeshifter | Marian’s shifting loyalties, Richard in disguise | Who or what has surprised you? |

| Shadow | Prince John, Gisbourne, the Sheriff | What are your greatest adversaries? |

| Ally | Much, Will Scarlet, Little John, Marian | Who stands by you? |

| Trickster | Robin’s wit, the archery disguise | How do you use humor or cunning? |

| Lover | Marian, Robin’s devotion to his people | What do you love enough to fight for? |

| Creator | Robin’s plans, the outlaw community | What have you built from nothing? |

| Ruler | Robin’s leadership, Richard’s return | Where do you lead or influence others? |

| Sage | Lessons learned, wisdom gained | What truths have you discovered? |

Exercises: Exploring Your Own Hero’s Journey

- Map Your Spiral: Draw a spiral and label each turn with an archetype you’ve encountered. Where do you see patterns repeating? Where have you grown?

- Write Your Legend: Begin your story: “Once upon a time, I…” Let the archetypes guide your narrative. Who are your allies? Your shadows? Your mentors?

- Identify Your Ordeal: What challenge has defined your journey so far? How did you face it? What archetypes helped or hindered you?

- Claim Your Elixir: What is the gift, insight, or strength you bring back to your world? How will you share it?

- Ask Yourself:

- Where am I on my journey?

- What archetype do I embody now?

- What legend am I creating-or avoiding?

You Are the Storyteller of Your Own Life

Robin Hood’s journey is a spiral of courage, wit, love, and transformation. So is yours. The 12 archetypes-Hero, Mentor, Shadow, and more-are not just characters in a legend, but living energies in your own story. You are the storyteller. You can create your own legend-or let others write it for you.

“May I obey all your commands with equal pleasure, sire.”

-Robin Hood, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)1

Will you answer your call to adventure? Will you spiral onward, learning, growing, and returning home transformed? The story is yours to tell.

It’s a Wonderful Life

The hero’s journey is more than a storytelling device-it’s a map of transformation that echoes through myth, movies, and our own lives. In It’s a Wonderful Life, this journey spirals through the heart of George Bailey, revealing not only the classic 12-step structure but also the living, evolving dance of archetypes that shape every human story. Let’s explore how these archetypes spiral through George’s journey, and how you might recognize, question, and reshape your own legend.

The Spiral of the Hero’s Journey in It’s a Wonderful Life

Why spiral? Because the journey is not a straight line. We revisit old lessons with new eyes, face familiar fears at deeper levels, and discover that the hero’s path is a cycle-each revolution bringing us closer to self-understanding and mastery.

1. The Ordinary World: The Innocent and the Everyman

George Bailey begins in Bedford Falls, an “ordinary” man with big dreams and a good heart. The Innocent archetype appears in his youthful optimism and faith in a brighter future. The Everyman surfaces in his desire to belong, to be part of his family and community, and to do right by others.

Question for you: Where in your life do you feel “ordinary,” longing for something more? Where does innocence or a sense of belonging shape your choices?

Exercise: Write a paragraph about your own “Bedford Falls”-the place, routine, or community that feels most familiar. What dreams or longings stir beneath the surface?

2. Call to Adventure: The Explorer and the Hero

George’s call is literal-he wants to explore the world, build skyscrapers, and shake the dust of his small town from his shoes. The Explorer archetype urges him toward new experiences and self-discovery, while the Hero archetype emerges in his desire to prove himself and make a difference.

Question for you: What adventure calls to you, even if only in daydreams? What would you do if you weren’t afraid?

Exercise: List three “calls” you’ve heard in your life-opportunities, invitations, or ideas that sparked your curiosity or courage. Did you answer? Why or why not?

3. Refusal of the Call: The Everyman and the Caregiver

Life interrupts. George’s father dies, and George chooses duty over dreams, staying to run the Building and Loan. Here, the Everyman’s fear of standing out and the Caregiver’s urge to protect others clash with his personal ambitions.

Question for you: When have you put others’ needs before your own dreams? How did it feel?

Exercise: Write about a time you “refused the call.” What did you gain? What did you lose?

4. Meeting the Mentor: The Sage and the Caregiver

Mentors appear in many guises: George’s father, Uncle Billy, and ultimately Clarence the angel. The Sage archetype offers wisdom; the Caregiver offers support and belief in George’s goodness.

Question for you: Who has mentored you? What wisdom or encouragement changed your path?

Exercise: Write a letter (real or imaginary) to a mentor. Thank them for their guidance, and reflect on how their influence shaped your journey.

5. Crossing the Threshold: The Rebel and the Hero

George crosses into the unknown when he stands up to Mr. Potter and commits to saving the Building and Loan, sacrificing his own plans. The Rebel archetype surfaces in his defiance of the system; the Hero in his willingness to fight for his community.

Question for you: When have you taken a stand, even when it cost you something?

Exercise: Describe a “threshold” moment in your life-a decision or action that changed everything. What archetypes were at play?

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies: The Lover, the Caregiver, the Ruler, and the Shadow

George faces trials: financial crises, Mr. Potter’s schemes, and the needs of his family and friends. Allies like Mary (the Lover and Caregiver), and enemies like Potter (the Ruler and Shadow), shape his journey.

Question for you: Who are your allies and adversaries? What roles do they play in your story?

Exercise: Map out your “cast of characters.” Assign archetypes to the key people in your life. How do they help or hinder your journey?

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave: The Creator and the Lover

As George builds a life with Mary, renovates the Granville House, and raises a family, the Creator archetype emerges-he’s making something new from the ashes of old dreams. The Lover archetype is present in his devotion to Mary and his children.

Question for you: What have you created in your life-relationships, homes, projects-that reflects your deepest values?

Exercise: Write about a time you “approached the cave”-took a risk to create or nurture something meaningful.

8. Ordeal: The Shadow and the Magician

The darkest hour arrives when George faces ruin, disgrace, and despair. The Shadow archetype is embodied by Potter and by George’s own inner demons. The Magician appears as Clarence, who offers George a new perspective-a magical vision of a world without him.

Question for you: What “ordeal” has tested you to your core? What shadows did you face?

Exercise: Recall a crisis in your life. What “magic” or unexpected help appeared? How did it change you?

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword): The Sage and the Everyman

George’s reward is not wealth or fame, but the realization of his own worth and the love of his community. The Sage archetype brings enlightenment; the Everyman archetype reminds us that even “ordinary” lives are extraordinary.

Question for you: What is your true reward? What have you gained from your struggles?

Exercise: List the “treasures” you’ve found-insights, relationships, strengths-on your journey.

10. The Road Back: The Hero and the Caregiver

Restored to hope, George races home, ready to face consequences for Uncle Billy’s mistake. The Hero returns, willing to sacrifice for others; the Caregiver’s love is evident in his embrace of family and friends.

Question for you: When have you returned from a trial with new resolve? How did you share your gifts with others?

Exercise: Write about a time you “came back” from a setback. How did you use what you learned to help someone else?

11. Resurrection: The Magician and the Ruler

In the film’s climax, George is “resurrected” by the outpouring of love from his community. The Magician archetype transforms despair into joy; the Ruler archetype is redeemed through the collective power of the people, not Potter’s tyranny.

Question for you: What has “resurrected” you-given you new life after defeat?

Exercise: Imagine your own resurrection scene. What would it look like? Who would be there?

12. Return with the Elixir: The Sage, the Everyman, and the Lover

George returns “home” in every sense-grateful, wise, and surrounded by love. The Sage’s wisdom, the Everyman’s belonging, and the Lover’s devotion complete his spiral journey.

Question for you: What “elixir” do you bring back to your world? How are you changed?

Exercise: Write a letter to your future self, describing the gifts you hope to carry forward from your journey.

The 12 Archetypes: Spiraling Through the Story

Here’s how the 12 archetypes spiral through It’s a Wonderful Life, and how you might see them in your own life:

| Archetype | George’s Story Example | Your Story Reflection |

|---|---|---|

| Innocent | George’s childhood dreams | Where are you still innocent, hopeful? |

| Everyman | His desire to belong, be “normal” | When do you blend in or stand out? |

| Hero | Standing up to Potter, saving the Building & Loan | When have you acted with courage? |

| Caregiver | Sacrificing for family, helping others | Who do you nurture or protect? |

| Explorer | Longing to travel, see the world | What do you long to discover? |

| Rebel | Defying Potter, challenging the system | When do you break the rules? |

| Lover | Devotion to Mary, family, community | Who or what do you love most deeply? |

| Creator | Building homes, making a family | What have you built or created? |

| Jester | Light moments with friends, children | How do you bring joy or laughter? |

| Sage | Gaining wisdom, learning his worth | What have you learned from hardship? |

| Magician | Clarence’s intervention, new perspective | What “magic” has changed your view? |

| Ruler | Leadership in the community, facing Potter | Where do you wield power or influence? |

The Spiral Nature of the Journey

The journey is not a checklist-it’s a spiral. You revisit archetypes at different stages, each time with greater depth or new challenges. George faces the Hero, Caregiver, and Everyman again and again, each time transformed by his experiences. The same is true for you.

Question for you: Which archetypes recur in your life? How have they changed as you’ve grown?

Exercise: Draw a spiral. Mark each archetype along the path. Where are you now? Where have you been? Where might you go next?

You Are the Storyteller of Your Own Life

It’s a Wonderful Life reminds us: You are the hero of your own story. You can choose which archetypes to embrace, which lessons to learn, and which legends to create.

“Each man’s life touches so many other lives. When he isn’t around he leaves an awful hole, doesn’t he?” – Clarence

Question for you: What legend are you creating? What story do you want to tell?

Exercise: Write the first paragraph of your own “wonderful life.” Begin with: “Once upon a time, I…”

Final Reflection

The hero’s journey is not just for George Bailey. It’s for you. The spiral of archetypes-Innocent, Hero, Caregiver, Lover, Sage, and more-appears in every life, every challenge, every triumph. By recognizing these patterns, asking deep questions, and bravely writing your own story, you become the creator of your own legend.

Will you answer the call? Will you spiral onward, learning and growing, until you return home transformed?

The story is yours to tell.

The Godfather

Michael Corleone’s transformation in The Godfather is one of cinema’s most iconic journeys-a story that, while following the classic hero’s journey arc, subverts and deepens it through a spiral of recurring archetypes. Michael’s path is not a straight ascent or descent; rather, it is a series of cycles, each time revisiting and reinterpreting the 12 archetypes at new levels of complexity, power, and loss. In this exploration, we’ll walk through those archetypes as they manifest in The Godfather, illustrating the spiral nature of the journey, and invite you to reflect on your own life’s legend with questions and exercises designed to help you become the conscious author of your own story.

1. The Ordinary World: The Outsider’s Illusion

Michael Corleone’s journey begins at his sister Connie’s wedding, where he is the outsider-decorated war hero, college-educated, and determined to live an “American” life separate from his family’s criminal empire. He tells Kay, “That’s my family, Kay. It’s not me.” This is Michael’s ordinary world: a fragile illusion of normalcy, individualism, and separation from the shadows of his heritage.

Reflect:

- When have you felt like an outsider in your own life or family?

- What illusions or stories did you tell yourself to maintain distance from your origins?

Exercise:

Write a scene from your own “ordinary world.” Where were you? Who did you want to be? What did you hope to avoid or escape?

2. The Call to Adventure: Crisis and Responsibility

The call arrives violently: Vito Corleone, Michael’s father, is shot by rival gangsters. The family is thrown into chaos. Michael, who wanted nothing to do with the business, is pulled in by necessity and love. The call is not just to action, but to identity: Will Michael protect his father and family, or remain apart?

Reflect:

- What crisis or challenge forced you to reconsider your path?

- Did you answer the call, or try to ignore it?

Exercise:

List three turning points in your life when you were called to step up or change. What was at stake? How did you respond?

3. Refusal of the Call: Resistance and Denial

Michael initially refuses the call. He visits his father in the hospital, but insists to Kay and Tom that he is not involved. He clings to his outsider status, resisting the pull of family loyalty and the moral ambiguity of the Corleone world. Yet, the spiral draws him closer each time the family is threatened.

Reflect:

- When have you resisted change or responsibility?

- What were you afraid of losing?

Exercise:

Write about a time you said “no” to a challenge, only to find yourself drawn in anyway. What changed your mind?

4. Meeting the Mentor: Guidance and Legacy