Your story is your life. As human beings, we continually tell ourselves stories — of success or failure; of power or victimhood; stories that endure for an hour, or a day, or an entire lifetime. We have stories about our work, our families and relationships, our health; about what we want and what we’re capable of achieving. Yet, while our stories profoundly affect how others see us and we see ourselves, too few of us even recognize that we’re telling stories, or what they are, or that we can change them — and, in turn, transform our very destinies.

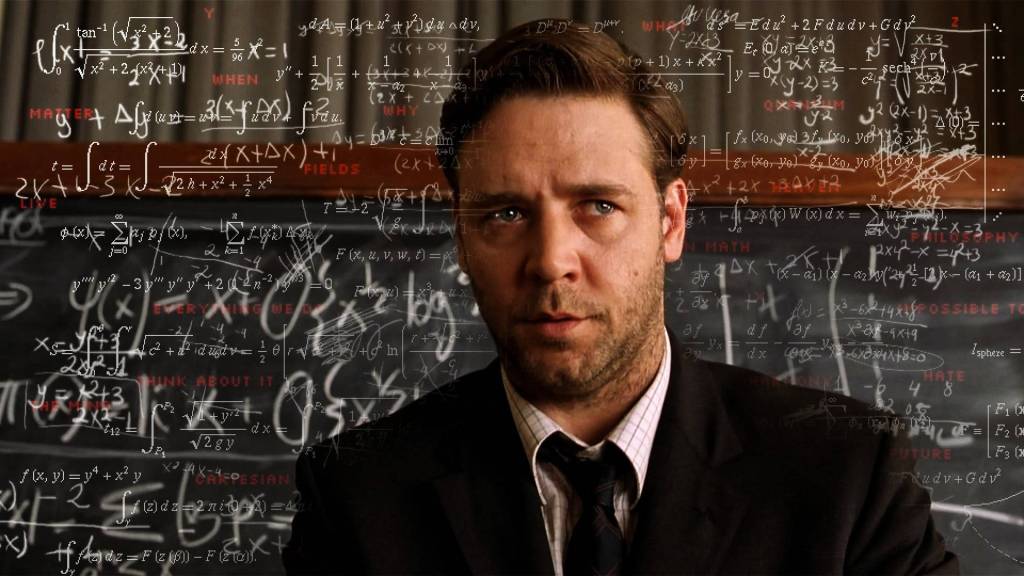

Your story is your life. A Beautiful Mind (2001), an Oscar-winning Best Picture, perfectly illustrates this truth through the harrowing journey of mathematician John Nash. Nash’s internal narratives—tales of genius, espionage, and isolation—initially propel him toward brilliance but spiral into delusion, nearly destroying his career, marriage, and sanity. The film reveals how unexamined stories shape our reality, echoing the idea that we tell ourselves tales of success or failure, power or victimhood, often without recognizing their power.

Nash arrives at Princeton as a prodigy obsessed with originality, crafting a story of himself as a solitary trailblazer destined for greatness. His breakthrough in game theory stems from this narrative, yet social awkwardness fuels a counter-story of rejection, breeding resentment toward peers and women he views as conquests. Schizophrenia shatters this fragile balance: hallucinatory figures like roomie Charles, agent Parcher, and niece Marcy embody his unmet desires for friendship, purpose, and innocence. These illusions become his reality, convincing him he’s decoding Soviet codes for the Pentagon—a gripping saga of heroic sacrifice that justifies paranoia and withdrawal from loved ones.

The pivot comes when wife Alicia uncovers the fabrications, forcing Nash to confront the chasm between his stories and truth. His descent peaks in rage and violence, as delusions demand he kill his family to “protect” them, mirroring how victimhood narratives sabotage health, relationships, and potential. Yet Alicia’s unwavering love challenges his script: she symbolizes the enduring power of authentic bonds, urging him to rewrite his tale. Nash learns to ignore hallucinations—not erase them—choosing a new narrative of resilience and integration. He returns to Princeton, teaches humbly, and earns the Nobel Prize, transforming victim into victor.

This evolution underscores the text’s core: our stories about work, family, and capabilities dictate destinies, but awareness allows change. Nash’s early arrogance evolves into empathy; he values collaboration over competition, love over logic. His Nobel speech celebrates Alicia’s devotion above intellect, proving rewritten stories heal. The film’s visual cues—desaturated tones for delusions, warm hues for recovery—reinforce this shift from shadowed isolation to luminous connection.

Ultimately, A Beautiful Mind warns that ignored inner dialogues breed chaos, but intentional retelling forges triumph. Nash’s arc—from prodigy undone by false epics to elder wise in reality’s quiet patterns—shows anyone can seize narrative reins. As he waves Alicia’s handkerchief post-speech, it signals not defeat, but destiny reclaimed through story’s alchemy. Love, perseverance, and self-awareness conquer even the mind’s fiercest fictions, affirming: change your tale, transform your life.

Telling ourselves stories provides structure and direction as we navigate life’s challenges and opportunities, and helps us interpret our goals and skills. Stories make sense of chaos; they organize our many divergent experiences into a coherent thread; they shape our entire reality. And far too many of our stories are dysfunctional, in need of serious editing. First, we ask you to answer the question, “In which areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I’ve got?” We then show you how to create new, reality-based stories that inspire you to action, and take you where you want to go both in your work and personal life.

For decades I have been examining the power of story to increase engagement and performance. Thousands of individuals from every walk of life have sought out and benefited from our life-altering stories.

Our capacity to tell stories is one of our profoundest gifts. My approach to creating deeply engaging stories will give you the tools to wield the power of storytelling and forever change your business and personal life.

Stories shape human experience like a compass that brings order to chaos. Three famous Oscar-winning movies—Good Will Hunting, The King’s Speech, and Forrest Gump—illustrate the profound role our personal stories play in directing our lives. Each film reveals how dysfunctional stories can hold us back and how revising those narratives leads to transformation. Through these films, it becomes clear that the stories we tell ourselves about our abilities, relationships, and purpose deeply influence our reality, shaping success or failure in both personal and professional life.

In Good Will Hunting (Best Original Screenplay, 1997), janitor Will Hunting embodies the chaos of a dysfunctional self-narrative rooted in childhood abuse and abandonment. Will tells himself a story of worthlessness and rage: he’s a brilliant mathematician hiding behind fists and sarcasm, convinced that vulnerability leads to betrayal. This tale organizes his experiences into a coherent thread of isolation—he sabotages jobs, relationships, and his genius potential, fearing true connection will expose his pain. The film’s core question hits hard: “In which areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I’ve got?” For Will, it’s everywhere—love with Skylar crumbles under his defenses, his intellect stagnates in menial work, and therapy fails until Sean Maguire pierces the armor. Sean’s raw empathy forces Will to confront his edited memories of trauma, revealing how they distort reality. By film’s end, Will crafts a new, reality-based story of self-worth and pursuit: he drives to chase love and opportunity, empowered to wield his gifts. This shift from victimhood to agency boosts engagement and performance, mirroring how therapeutic storytelling heals deep wounds.

Similarly, The King’s Speech (Best Picture, 2010) charts King George VI’s battle against a narrative of inadequacy forged by his stammer and royal pressures. Bertie (Prince Albert) views himself as a flawed failure, unfit for leadership—his story frames every stutter as proof of weakness, amplifying chaos into public humiliation. This dysfunctional script hampers his goals: commanding respect as king amid rising fascism seems impossible. He must interrogate: where does this story block progress? In duty, family, and self-image. Enter unconventional therapist Lionel Logue, who demands equality and excavates buried pains like parental rejection. Through exercises blending play, profanity, and honesty, Bertie rewrites his tale—from fearful mute to resilient voice. His triumphant wartime broadcast weaves divergent experiences (stammers, abdication crisis, therapy breakthroughs) into a coherent thread of authentic strength. This new narrative inspires national unity and personal purpose, proving stories provide structure for challenges while editing out self-doubt.

Forrest Gump (Best Picture, 1994) contrasts with optimism, showing a functional story mastering life’s unpredictability. Forrest’s simple narrative—”Mama always said life is like a box of chocolates”—interprets chaos through resilience, kindness, and presence. Low IQ and braces don’t define him; instead, he organizes ping-pong triumphs, war heroism, shrimping fortune, and Jenny’s loss into a thread of earnest action. No major dysfunction mars his tale—it’s reality-based, focusing on skills like loyalty and perseverance amid Vietnam, counterculture, and grief. When Lieutenant Dan rages against fate, Forrest’s steady story anchors him, fostering mutual growth. This empowers Forrest to run across America, inspire millions, and build a legacy of love (fathering Forrest Jr.). His arc teaches that empowering stories align goals with opportunities, turning divergent paths into directed triumph without needing overhaul.

Together, these films affirm storytelling’s gift: it structures chaos, interprets skills amid opportunities, and drives performance. Dysfunctional narratives—like Will’s trauma armor or Bertie’s fear—demand editing via self-questioning and reality checks. Forrest’s resilient simplicity shows proactive tales prevent stagnation. Asking “Where is my story failing me?” unlocks new scripts that propel work (Nash-like genius unleashed, royal duty fulfilled) and personal realms (love embraced, bonds healed). Thousands have transformed through such shifts, as storytellers like Logue or Sean demonstrate. Wielding this power—crafting engaging, action-oriented narratives—forever alters trajectories, turning life’s box of chocolates into purposeful adventure.

Day 1. That’s Your Story?

Day 2. The Premise of Your Story, the Purpose of Your Life

Day 3. How Faithful a Narrator Are You

Day 4. Is It Really Your Story You’re Living?

Day 5. The Private Voice

Day 6. The Three Rules of Storytelling

PART TWO

New Stories

Day 7. It is not about time

Day 8. Do You Have the Resources to Live Your Best Story?

Day 9. Indoctrinate Yourself

Day 10. Turning Story into Action: Training Mission and Rituals

Day 11. More than Mere Words; Finishing the Story, Completing the Mission

Day 12. Storyboarding the Transformation Process in Eight Steps

Introduction

I am Peter de Kuster, founder of The Hero’s Journey and The Heroine’s Journey, and for much of my life, I have believed in the transformative power of stories—especially the ones we tell ourselves. But it took a near-death experience to truly open my eyes to what I wanted to dedicate my life to: helping others discover, shape, and share their unique stories, and in doing so, to rewrite my own.

Lying in that hospital bed, suspended between what was and what could be, I realized how fragile and precious life is. All the plans, the business meetings, the deadlines—they faded into insignificance. What remained was a burning question: What story do I want to tell with the rest of my life? The answer was clear. I wanted to travel, to write, to tell stories.

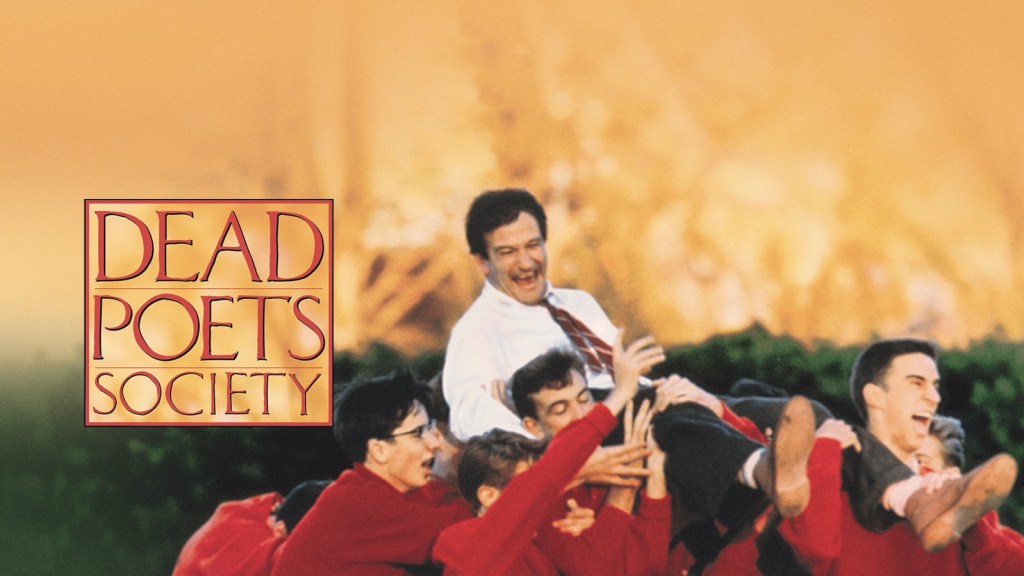

There is a language older than words that has always fascinated me. It speaks in images and emotions, in the quiet tightening of a throat in a dark cinema, in the sigh when the credits roll and you realize the story on the screen has quietly rewritten a sentence in the story you tell about yourself. Like in Dead Poets Society, where students seize the day, ripping out textbook pages to embrace poetry’s raw power over conformity, sparking personal rebellion and self-discovery. That is the language I am searching for with The Power of Your Story: a universal language of stories that crosses borders, backgrounds, and biographies, and invites each of us to become a better storyteller of our own life.

My quest runs through movie palaces in Rome, side streets in London, quiet museums in Venice, and cafés in Amsterdam, where people sit with notebooks, watching scenes from great films and quietly recognizing themselves. In these story-rich places, I walk with entrepreneurs, artists, and seekers who arrive with a familiar question hidden behind their official goals: “Why does the story I am living not feel like mine anymore?” Together we watch heroes and heroines on the screen and notice that, beneath costume and culture, they share something startlingly similar: seven great plots, twelve archetypal heroes, and again and again one great story about leaving an old life behind to claim a truer one.

What fascinates me is how the same story patterns keep appearing in people who have never met. A designer in Berlin talks like a Warrior exhausted by endless battles for recognition. A chef in Barcelona feels like the Orphan, forever on the edge of belonging. A startup founder in Paris discovers she has been living the Ruler’s story of control when her heart longs for the Explorer’s open road. Then we sit in a cinema and watch a character in a film struggle with the very same script. In La Vita è Bella, a father shields his son from Holocaust horrors by framing camp life as an enchanted game, turning despair into defiant love and survival. In that moment, the language of story becomes universal: you no longer feel uniquely stuck; you feel spoken to. The film is no longer “about” someone else. It is a mirror, gently asking: “Is this the story you still want to live?”

In The Power of Your Story, I always begin with one question: “In which areas of your life is it clear that you cannot achieve your goals with the story you’ve got?” It is a brave question because it exposes the hidden contracts we live by: “I must always please,” “I must never fail,” “I am only valuable when I achieve.” As people answer, you can feel the old plot loosening its grip. Then, using the archetypes and classic plots from film, we start drafting a new premise: What if your life is not a tragedy of overwork but a quest for meaningful creation? What if your business is not a battlefield but a love story with your best customers? What if your leadership is not about power but about pilgrimage—inviting others on a journey that matters?

Movies help because they condense a lifetime of trial and error into two hours of heightened truth. When you see a character cling to the wrong story and lose everything, you recognize your own flawed alignment; when you see them question their premise and realign, you glimpse what might be possible for you. In The Game, Nicholas Van Orton unravels his rigid control narrative through a chaotic “game” that strips illusions, forcing rebirth from existential void. In Rome or Venice, walking from cinema to café, we translate those cinematic moments back into the language of everyday decisions: Which clients do you choose? How do you speak about your work? What do you tolerate in your calendar that you would never accept in your favorite film’s final act?

What this quest can bring all of us is not a neat formula, but a toolkit and a courage. The toolkit consists of questions and structures: the premise of your story, the words on your future tombstone, the mission you dare to say out loud, the archetype that best expresses your values, the plot that truly fits the season of life you are in. The courage comes from realizing you are not alone: every great story, every great business, every meaningful relationship has had to rewrite itself at some point. When you start to see your life as a work in progress rather than a verdict, you reclaim authorship. You stop asking, “What is happening to me?” and start asking, “What story am I telling—and what story do I want to tell next?”

The universal language of stories is, in the end, a language of choice. You cannot control every event, every loss, every unexpected twist. But you can choose the story that gives those events meaning. My work, and my joy, is to walk with people through the great cities and great movies of the world until they can hear that language clearly in themselves. When they do, something simple and astonishing happens: they stop trying to live someone else’s script. They become the storyteller, not just the character. And from that moment on, their business, their relationships, and their inner life begin to align around a new, truer story—one only they can tell.

What do I mean by ‘story’?

What do I mean by ‘story’? I don’t intend to offer tips on how to fine-tune the mechanics of telling stories to enhance the desired effect on listeners. And I do not mean the boiler-plate, holier-than-thou brand stories often found in the Mission Statement of corporate websites, or the Here’s -why-we’ll – absolutely-meet-our-fourth-quarter numbers-narrative-yarn-turned-pep-rally that team leaders often like to spin to rally the troops.

No, I wish to examine the most compelling story about storytelling – namely how we tell stories about ourselves to ourselves. Indeed, the idea of ‘one’s own story’ is so powerful, so native, that I hardly consider it a metaphor, as if it’s some new lens through which to look at life. Your life is your story. Your story is your life. When stories we read or watch or listen to are triumphant, they are so because they fundamentally remind us what is most true or possible in life – even when it is an escapist romantic comedy or sci-fi fantasy or fairy tale. If you are human, then you tell yourself stories – positive ones and negative, consciously and, far more than not, subconsciously. Stories that span a single episode, or a year, or a semester, or a weekend, or a relationship, or a season, or an entire tenure on this planet. Telling ourselves stories helps us navigate our way through life because they provide structure and direction. ‘Just seeing my life as a story’ said one of my clients ‘allowed me to establish a sort of road map, so when I have to make decisions about what I need to do [the map] makes it easier, takes away a lot of stress’.

Consider Big Fish (2003): Edward Bloom weaves mythic quests from mundane days, subconsciously navigating love, fear, legacy. His son Will rejects “lies” for facts—until reconciliation proves narrative trumps literalism, turning ordinary into epic Hero’s Journey.

Or Moonlight (2016): Chiron’s silent chapters reshape identity through trauma’s inner scripts—from shame to resilient strength, a roadmap amid chaos.

Like The Insider (1999), where whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand shatters corporate illusions, rewriting his ethical tale against deceit. These films mirror our quest: ditch limiting stories. Own your narrative—premise, turning points, archetypes. As in Gladiator’s redemption arc, re-author for courage, wholeness.

Indeed we are actually wired to tell stories: The human brain, according to a New York Times article about scientists investigating why we think the way we do, has evolved into a narrative-creating machine that takes ‘whatever it encounters, no matter how apparently random’ and imposes on it ‘chronology and cause-and-effect logic’. Writes Justin Barrett, psychologist at Oxford University, ‘We automatically and often unconsciously look for an explanation of why things happen to us and ‘stuff just happens’ is no explanation’ (which feeds one possible theory for why we need, or even create, God or Gods). Stories impose meaning on the chaos; they organize and give context to our sensory experiences, which otherwise might seem like no more than a fairly colorless sequence of facts. Facts are meaningless until you create a story around them.

Slumdog Millionaire (2008): Oscar Winner on Narrative from Chaos

Slumdog Millionaire, Best Picture winner sweeping eight Oscars, captures our brain’s narrative machinery turning random horrors into destined epic. Jamal Malik (Dev Patel), Mumbai slum survivor, faces game show scrutiny: each question pulls “apparently random” traumas—blinded mom, child labor, blinding betrayal—into chronological cause-effect revelation. Facts (poverty, loss) stay colorless until his subconscious story imposes meaning: life’s quiz scripted for love’s reunion with Latika (Freida Pinto). Jamal unconsciously forges “why”: childhood games predict quiz answers, police torture demands destiny’s proof. Stories organize sensory chaos: beggar scams gain context as survival lore, Quiz Master’s cynicism crumbles under Jamal’s mythic arc. No god needed; narrative creates one. Spanning episodes (seasons of orphanage, train-top flights), Jamal’s tale reminds us of possibilities—slumdog to millionaire—proving stories color drab sequences with vibrant purpose. Triumph erupts in finale’s dance, affirming wiring for chronology: randomness yields roadmap from void to victory. Watch it; reclaim your chaos as legend.

A story is our creation of a reality; indeed our story matters more than what actually happens. Is there really any difference, as someone famously asked, between the life of a king who sleeps twelve hours a day dreaming he’s a pauper, and that of a pauper who sleeps twelve hours a day dreaming he’s a king?

By ‘story’ I mean those tales we create and tell ourselves and others, and which form the only reality we will ever know in this life. Our stories may or may not conform to the real world. They may or may not inspire us to take hope – filled action to better our lives. They may or may not take us where we ultimately want to go. But since our destiny follows our stories, it is imperative that we do everything in our power to get our stories right.

For most of us, that means some serious editing.

To edit a dysfunctional story, you must first identify it. To do that you must answer the question: In which important areas of my life is it clear that I cannot achieve my goals with the story I have got? Only after confronting and satisfactorily answering this question can you expect to build new reality – based stories that will take you where you want to go.

Is this all starting to sound a little vague? I’m not surprised. But hold on. I understand you may be thinking Life as a story? The whole concept strikes you, perhaps, as a tad …. soft. I don’t look at my life in terms of story, you say. I disagree. Your life is the most important story you will ever tell, and you are telling it right now, whether you know it or not. From very early on you are spinning and telling multiple stories about your life, publicly and privately, stories that have a theme, a tone, a premise – whether you know it or not. Some stories are for better, some for worse. No one lacks material. Everyone’s got a story.

The Pursuit of Happyness, starring Will Smith as Chris Gardner, powerfully illustrates identifying and editing life’s core story for goal achievement. Stranded homeless with son Christopher amid unpaid bills and failed sales gigs, Chris clings to a dysfunctional premise: “I’m a failure doomed by bad luck”—blocking career dreams, stability. Therapist-like mentors and self-confrontation force the question: “In jobs, fatherhood, survival—where does this story fail me?” Only then does he rewrite for reality-based triumph. From early spins—public boasts masking private despair, tones of victimhood—Chris’s yarn spans episodes: internship rejections, shelter lines. Vague “soft” concepts? No—life’s material screams dysfunction everywhere goals elude. “Your story’s the most important you’ll tell,” echoes his arc; unrecognized themes sabotage now, demanding confrontation before new builds. Post-identification, Chris authors afresh: premise shifts to “Relentless grind wins,” toning persistence across seasons of hunger, exams. Bone density scanner hustles become metaphors for unyielding quest; internship yields stockbroker breakthrough. Everyone’s got stories—better or worse—but editing unlocks destinations. Chris proves: answer the hard question, rebuild boldly.

And thank goodness. Because our capacity to tell stories is, I believe, just about our profoundest gift. Perhaps the true power of the story metaphor is best captured by this seemingly contradiction: we employ the word ‘story’ to suggest both the wildest of dreams (it is just a story ……) and an unvarnished depiction of reality (okay, what is the story?). How is that for range?

The challenge? Most of us are not writers. ‘I am not a professional novelist’ one client said to me, when finally the time came for him to put pen to paper. ‘If this is the story of my life, you are damn right I’m intimidated. Can you give me a little help in how to get this out? That’s what I intend to do with the Hero’s Journey and The Heroine’s Journey project. First, help you to identify how pervasive the story is in life, your life, and second, to rewrite it.

Every life has elements to it that every story has – beginning, middle, and end; theme; subplots; trajectory; tone.

In mythology, the story of Odysseus provides a profound analogy for how we can understand the development of true talent. Odysseus, on his long journey home from Troy, knew that every stage of his voyage would bring at least one troublesome challenge—whether it was the wrath of the gods, the lure of the Sirens, or the monstrous Cyclops. What distinguished Odysseus was not just his skill or cunning, but a deep sureness that his journey was part of a compelling and enduring story embedded deep within his psyche. This story gave him the strength to face adversity with courage and resilience.

Similarly, in any professional pursuit—whether in sports, the arts, or entrepreneurship—there will always be at least one troublesome moment in every round, every project, every endeavor. The key to true mastery is not to avoid these moments but to expect them and to understand that they are integral to the journey. Talent develops not merely through flawless execution but through the confidence that comes from knowing one’s story is larger than any single setback.

This sureness, this inner narrative, becomes a guiding force. It transforms challenges from obstacles into meaningful trials that test and deepen one’s character. When a person embraces this perspective, each difficult moment becomes an opportunity for growth rather than a cause for doubt. The development of talent, then, is inseparable from the power of a compelling story—one that endures, shapes identity, and fuels perseverance through every troublesome shot life presents.

Story is everywhere in life. Perhaps your story is that you are responsible for the happiness and livelihoods of dozens of people around you and you are the unappreciated hero. If you see things in more general terms, maybe your story is that the world is full of traps and misfortune – at least for you – and you’re the perpetual victim (I’m always so unlucky…. I always end up getting the short end of the stick…. People can’t be trusted and will take advantage of me if I give them the chance.).

If you are focused on one subplot – business say – then maybe your story is that you sincerely want to execute the major initiatives in your company, yet you are restricted in some essential way and thus can never get far enough from the forest to see the trees. Maybe your story is that you must keep chasing even though you already seem to have a lot (even too much) because the point is to get more and more of it – money, prestige, power, control, attention. Maybe your story is that you and your children just can’t connect. Or your story might be essentially a rejection of another story – and everything you do is filtered through that rejection.

Stories are everywhere. Your body tells a story. The smile or frown on your face, your shoulders thrust back in confidence or slumped roundly in despair, the liveliness or fatigue in your gait, the sparkle of hope and joy in your eyes or the blank stare, your fitness, the size of your gut, the tone and strength of your physical being, your overall presentation – those are all part of your story, one that’s especially apparent to everyone else. We judge books by their covers not simply because we are wired to judge quickly but because the cover so often provides astonishing accurate clues to what is going on inside. What is your story about your physical self? Does it truly work for you? Can it take you where you want to go in the short term? How about ten years from now? What about thirty?

In the sweltering jury room, Juror 8 embodied the unappreciated hero, shoulders thrust back against the weight of eleven men’s hasty verdicts, responsible for a slum boy’s life—their livelihoods hanging on his solitary doubt. His story defied the group’s victim trap: a world of misfortune where the kid got the short end, untrusted slum spawn ripe for exploitation. “Open-and-shut,” they chorused, chasing quick escape like prestige in a ballgame subplot, restricted by bias’s forest, blind to evidence trees. Father-son rifts echoed—Juror 3’s fractured bond fueling rage—while bodies told tales: slumped despair in sweat-soaked shirts, fatigued gaits pacing fury, blank stares of prejudice, guts straining under heat’s tone, covers judging the kid guilty before deliberation.

Heat’s verdict sparked rejection of the mob narrative. No cabaret cool-down; Juror 8’s calm spark—knife demo, timeline flaws, glasses marks—ignited hope’s swing. Shoulders unslumped across the room, eyes sparkling with reason’s joy, strides lively as votes flipped from prey to justice. From cesspool bigotry, he built a playground of doubt, saving the boy from the chair. The others marveled post-unanimous not guilty, toasting over rain-cooled coats, vowing fairness they’d forget in comfort. Dozens beyond the door owed this unseen heroism.

Juror 8’s stand screams in your story: frowns trapping “unlucky” slouches, fitness fading under despair’s gut. Does your physical cover propel short-term truth, or chain you in ten years? Thirty? Bodies clue inner scripts—strengthen tone, ignite gaze, present confident. Stories permeate life; rewrite the verdict now. Reject victim haste; deliberate glory like him. Your presentation leads—make it acquit your potential, not condemn it.

You have a story about your company, though your version may depart wildly from your customer’s or business partners. You have a story about your family. Anything that consumes our energy can be a story, even if we don’t always call it a story. There is the story of your relationship. The story of you and food, or you and anger, or you and impossible dreams. The story of you, the friend. The story of you, your father’s son or your mother’s daughter. Some of these stories work and some of them fail. According to my experience, an astounding number of these stories, once they are identified, are deemed tragic – not by me, mind you but by the people living them.

Like it or not, there will be a story around your death. What will it be? Will you die a senseless death? Perhaps you drank too much and failed to buckle your seat belt and were thrown from your car, or you died from colon cancer because you refused to undergo an embarrassing colonoscopy years before when the disease was treatable. Or after years of bad nutrition, no exercise, and abuse of your body, you suffered a fatal heart attack at age fifty – nine. ‘Senseless death’ means that it did not have to happen when it happened; it means your story did not have to end the way it ended. Think about the effect the story of your senseless death might have on your family, on those you care about who you are leaving behind. How would that story impact their life stories? Ask yourself, Am I okay dying a senseless death? Your immediate reaction is almost certainly, “No!, of course not!

I’m not trying to be morbid. Story – which dies if deprived of energy – is not about death but life. Yet if you continue to tell a bad story, if you continue to give energy to a bad story, then you will almost assuredly beget another bad one, or ten. Why is abuse so commonly passed from one generation to the next? How much is the recurrence of obesity, diabetes and certain other diseases across families a genetic predisposition, and how much is the repetition of a dangerous story about food and physical exertion.

One of the most enduring examples of how bad stories persist through generations is the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. This chilling German folktale, first chronicled in the Middle Ages and immortalized by the Brothers Grimm, tells of a town plagued by rats. The citizens, desperate for relief, hire a mysterious piper who drives the vermin away with his magical music. But when the townspeople refuse to pay him, the piper returns and lures away their children, who are never seen again. The tale has been retold for centuries, its details shifting with each generation, but always retaining its dark core: a community’s broken promise leading to a terrible loss.

The Pied Piper story is a classic example of how disturbing myths can outlast their origins. While some historians speculate that the tale may have roots in a real event—perhaps a mass migration or a tragedy that befell the town’s youth—the myth has grown far beyond any factual basis. Its endurance owes much to its unsettling themes: betrayal, punishment, and the vulnerability of children. These elements resonate across cultures and eras, ensuring the story’s survival even as its original context fades.

Such stories persist because they tap into deep-seated fears and moral anxieties. The Pied Piper warns of the consequences of breaking promises and the dangers lurking in the unknown. Its longevity shows how bad stories—those that unsettle, frighten, or caution—can become embedded in collective memory, passed down not just for entertainment, but as warnings or explanations for inexplicable events. In doing so, they shape cultural attitudes and even influence real-world behavior for generations

Unhealthy storytelling is characterized by a diet of faulty thinking and, ultimately, long – term negative consequences. This undetectable, yet inexorable progression is not unlike what happens to coronary arteries from a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet. In the body, the consequence of such a diet is hardening of the arteries. In the mind, the consequence of bad storytelling is hardening of the categories, narrowing of the possibilities, calcification of perception. Both roads lead to tragedy, often quietly.

The cumulative effect of our damaging stories will have tragic consequences on our health, engagement, performance and happiness. Because we can’t confirm the damage our defective storytelling is wreaking, we disregard it, or veto our gut reactions to make a change. Then one day we awaken to the reality that we have become cynical, negative, angry. That is now who we are. Though we never quite saw it coming, that is now our true story.

It is not just individuals who tell stories about themselves; groups do it, too. Nations and religions and universities, companies and sports teams and political parties each tell stories about themselves to capture the imagination of their constituencies. Companies tell their stories to engage their customers and, increasingly, their workforce, stories which must be internally consistent and powerful if they’re to succeed over time.

Few myths illustrate the power of branding your story as effectively as the legend of King Arthur and the Sword in the Stone. While tales of chivalric kings and magical swords abound in world mythology, the Arthurian legend stands out because of how its core elements—Arthur, Excalibur, Camelot, and the Round Table—have been carefully shaped, named, and repeated over centuries, turning them into instantly recognizable symbols.

The story goes that Britain was in chaos after the death of King Uther Pendragon. In the midst of this turmoil, a mysterious sword appeared, embedded in a stone, bearing the inscription that only the rightful king could pull it free. Many tried and failed, but the young and unassuming Arthur succeeded, revealing his destiny. This simple but powerful narrative, with its clear hero, magical object, and dramatic test, has been retold in countless forms, from medieval romances to modern films.

What sets the Arthurian myth apart is how its branding—the names, symbols, and motifs—have been meticulously cultivated. The very name “Excalibur” evokes images of heroism and destiny. Camelot conjures a utopian kingdom of justice and equality. The Round Table, with its emphasis on equality among knights, became a symbol for fair leadership. Over time, storytellers and chroniclers added layers to the legend, reinforcing these branded elements until they became cultural shorthand for ideals like nobility, honor, and rightful rule.

The enduring success of the Arthurian legend demonstrates that branding isn’t just for products—it’s essential for stories, too. By attaching memorable names and symbols to its core themes, the myth became more than a tale; it became a cultural touchstone, instantly recognizable and endlessly adaptable, proving the lasting power of a well-branded story.

Throughout this seminar I will detail how such organizations and their employees have reworked their story to the great advantage of both their business and their culture.

For twenty-five years I have studied human behavior and performance, and been privileged to witness many success stories of positive behavioral change: better relationships at home and at work, better job performance, weight loss and all-around improved health and lowering of health risks; love, excitement, joy and the discovery of talents heretofore buried. My experience has led me to see that these changes may be brought about by a unique integration of all the human sciences.

Over the past 30 years, my work has been deeply rooted in exploring flow experiences—those moments of deep engagement and creativity where challenge meets skill perfectly, as described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. What I have discovered is that flow is not just a psychological state but a transformative journey, especially when combined with the power of storytelling. Storytelling provides the narrative framework that helps individuals and leaders make sense of their experiences, integrate their passions, and sustain flow beyond fleeting moments.

In my leadership journeys I use storytelling archetypes to create conditions that naturally foster flow. These timeless narrative structures help participants embody roles and challenges that align with their skills, creating a balance that triggers flow states. Storytelling here is not just decoration—it is a tool for meaning-making and motivation, enabling people to connect their personal and professional challenges to a larger, inspiring narrative.

Client feedback has been essential throughout this journey. From the earliest workshops to the latest leadership retreats, I have consistently integrated participant reflections and stories to refine the frameworks and exercises. This iterative process ensures that the storytelling methods remain relevant, practical, and deeply resonant. Clients often report that framing their challenges within a story helps them gain clarity, see new possibilities, and sustain the passion that fuels flow. Their feedback has confirmed that storytelling is the bridge between abstract flow theory and real-world application, making flow accessible and sustainable in everyday leadership and creative work.

In sum, my three decades of work show that flow and storytelling are inseparable partners. Flow offers the experience of peak engagement, while storytelling provides the narrative structure that helps individuals understand, sustain, and share that experience meaningfully. This synergy, continuously refined through client collaboration, is at the heart of my approach to leadership and creativity.

Chocolate: A Story of Flow and Transformation

In the quiet French village touched by tradition and tension, Vianne Rocher’s story began as an act of gentle rebellion—a stranger opening a chocolate shop that quickly became a conduit for flow and transformation. Vianne’s skill met challenge perfectly, creating a space where the art of chocolate-making awakened passion, creativity, and joy in others. Her story wasn’t just about sweets but about balancing skill and challenge, inviting others into moments of deep engagement that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls flow.

Vianne’s presence stirred the village, including a mayor rigid in control and townsfolk bound by old stories of fear and suspicion. Through her storytelling and the magic of chocolate, she offered new narratives—of connection, hope, and possibility—that helped people reimagine their lives. Her subtle leadership created the conditions for flow not only in her craft but in the hearts and behaviors of those around her, fostering a culture of openness and transformation.

Her journey illustrates how flow is more than personal psychology; it’s a collective narrative journey. Storytelling framed challenges not as threats but as adventures aligned with individual and communal strength. Vianne’s chocolate shop became a symbol of meaning, motivation, and engagement—a shared story that sustained passion well beyond fleeting moments of delight. The interplay of skill and challenge, wrapped in storytelling archetypes, enabled the village to rewrite its collective story, ultimately transforming business and culture alike.

This story of flow and storytelling synergy offers leadership lessons: authentic connection to purpose, engagement through narrative, and the creation of shared myths that propel change. Like Vianne, leaders and organizations can harness this integration to unlock both peak performance and profound cultural shifts, sustained by stories that resonate deeply and inspire continually.

Of course, some people who have travelled with me on the Power of your Story are utterly unaffected by what we do and what they’re exposed to. Why? Some feel their ‘story’ needs no major reworking (and perhaps they’re absolutely right). Some fail to buy in to what we do because they’re just moving too fast. For some, the timing isn’t right (though, as I intend to show, it is always the right moment to change: now). Whatever the reason, for virtually every group I encounter 20% – the percentage is like clockwork – are simply not interested in what we have to say.

I respect that. The Power of Your Story was not designed to push an agenda. While I passionately believe that the story metaphor is universal and, with awareness, can be extraordinarily beneficial, it ‘works’ only when the individual is willing to look hard at the major problem areas in his or her life, explore why they’re problems, then meaningfully change the problem elements, be they structure or content, which are causing a profound lack of productivity, fulfillment, engagement, and sense of purpose. We work with people. We don’t stand over them and make them do something they don’t want.

Unlike many practitioners in the field of performance improvement , I do not believe you can have it all. It’s an absurd proposition. I don’t believe that every day will be a great day, that you can eliminate regret and despair and worry, that you will always be moving forward, that you will always succeed, that you won’t veer off track again. I do believe that you can have what is most important to you. And that this is achievable if you’re willing to follow the steps of the process advocated in this seminar.

Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita embodies a profound exploration of the human story—not one of pushing a fixed agenda but inviting reflection on what anchors or fragments our lives. Marcello Rubini, a society journalist drifting through Rome’s glittering but hollow nightlife, shows us how stories shape our engagement with life’s meaning and purpose. This is not a tale of having it all—an absurd ideal—but of the struggle to find what matters most amid chaos, regret, and fleeting pleasures. Marcello’s story challenges us to look deeply at our own problem areas, to explore why they block fulfillment, and to discover what shifts are needed to break free.

Throughout the film, Marcello oscillates between chasing the elusive ‘sweet life’ and confronting profound emptiness—his relationships, career, and desires ensnared in cycles of distraction and disillusionment. His encounter with the glamorous but unattainable Sylvia, the intellectual yet tragic Steiner, and the innocent Paola each reflect chapters in his fragmented narrative. Marcello’s journey is a reminder that meaningful change demands courage to notice when we stray, admit where we are lost, and embrace the discomfort of transformation. He cannot force change; instead, his story unfolds in hesitant steps, and so must ours.

This film illustrates how storytelling—when wielded with awareness—offers a framework for facing life’s essential questions, integrating passions, and navigating setbacks. It underscores that the goal is not perfection or constant progress but to claim what is most vital to us, even amid failure and wavering. Marcello’s muted gestures—the shrug to Paola’s call, the silent embrace of loss, the restless pacing in emptiness—speak volumes about the stories our bodies tell. They remind us that our outer presentation often mirrors inner turmoil or possibility. The power lies in being willing to re-author the script with honesty and resolve.

In leadership and life, La Dolce Vita teaches that the power of our stories grows when we align them with authenticity and self-awareness rather than illusions. It calls for embracing complexity, rejecting the fantasy of ‘having it all,’ and choosing instead to cultivate what truly sustains us. Marcello’s path is an archetype: the seeker who must acknowledge loss and limitation before glimpsing meaning. Ours is the choice to follow this journey, step by step, with grace and awareness, crafting stories that nurture rather than deplete our hearts and souls.

Who are the people who come to the Power of Your Story with dysfunctional life stories that need serious editing? They are, simply put, among the smartest, most talented, most ambitious, most creative people in their communities and professional circles. Some participants even bring, or return with spouses, friends or parents. They tend to have lots of responsibilities, they’re accountable for a great deal that goes on in their companies, they often make lots and lots of money….. yet, perhaps ironically, for all their accomplishments they can’t seem to get their stories right. On the questionnaire I ask clients to fill out before they come down to a world city for our two – and – a – half – day journeys (or to the one and two day events we conduct around the world) they are asked, among other things, to write down some of the most important parts of their life story. ‘My father died young of emphysema’, wrote the CEO of his family’s company. Later on the questionnaire, he wrote ‘I smoke two packs a day.’ Still later, describing one of his goals for the now fifty-year-old company, he wrote, ‘On the evening celebrating our company’s seventy-fifth anniversary, I want to be able to look back on yet another quarter century of quality, growth and profitability’.

How can these three sentences follow from each other without their author acknowledging that, taken together, they add up to utter nonsense? Especially when the author is superbly gifted in so many other areas?

‘The most important thing in my life is my family, wrote one client ‘and if things continue in the direction they’re going, I’m almost certainly heading for divorce and complete estrangement from my children’.

I’ll give him this much: At least he saw the tragedy coming.

In a previous book I argued that one of our biggest problems is rooted in our flawed belief that simply investing time in the things we care about will generate a positive return. That belief and the story that flows from it are simply not true. We can spend time with our families, be present at dinnertime, have lunches with our direct colleagues, remember to call home when traveling, put in 45 minutes on the treadmill five days a week – we can all do all of it but if we’re too exhausted, too distracted, too frustrated and angry when ‘doing’ these things, the positive return we hoped for will simply not materialize. Without investing high-quality, focused energy in the activity before you, whatever it may be, setting time aside simply takes us from absenteeism to presenteeism.

Warren Schmidt’s story in About Schmidt lays bare the silent plague of presenteeism, that vague malady where entrepreneurs—and all of us—drag impaired selves through the day, medically, physically, or psychologically compromised. For decades, Warren clocked in as an actuary at Woodmen of the World, his mind adrift in fatigue, his energy sapped by routine’s dull grind. Retirement hit like a void: no plans, just a drooping face and world-weary slump, haunting his Omaha home. Was this “present” Warren truly better than absent? As spouse to Helen, father to Jeannie, he haunted roles without vitality, time wasted without energy’s spark. Time holds value only at energy’s intersection—priceless when fused with full engagement, flow, or bliss. Warren embodied the opposite: a ghost in his own life.

Helen’s sudden death from a brain clot shattered his inertia. Dumping her belongings after discovering her old affair, he fired up the Winnebago, chasing his daughter’s wedding in Denver to derail her union with waterbed salesman Randall. Along the interstate, presenteeism morphed into raw confrontation. Visiting his old office, he saw his files trashed—useless relics. Camping under stars, a meteor streaked as he forgave Helen, apologizing for his failings. Energy flickered: not constant bliss, but glimmers of purpose. Yet Roberta’s hot tub advance repelled him, back thrown out on Randall’s bed, exhaustion fueling fury at Jeannie’s choices. He ranted to foster child Ndugu in letters, venting irrelevance: “My life made no difference.”

The wedding crystallized his malaise. Surrounded by Randall’s eccentric clan, Warren hid disapproval in a kind speech, fleeing depleted. Driving home, final letter to Ndugu questioned legacy: soon dead, erased. Yet Ndugu’s simple drawing—a child’s sun—pierced despair. Warren glimpsed full engagement’s promise: not every day triumphant, but energy reclaiming time. Presenteeism’s trap—impaired performance as parent, spouse, self—demanded rewrite. Flow awaited where challenge met renewed skill, not zombie endurance.

Schmidt’s odyssey whispers to entrepreneurs: fatigued presence poisons more than absence. Bliss blooms in energy’s surge, transforming time into legacy. Warren didn’t “have it all”—regret lingered, tracks veered—but he touched what mattered: honest reckoning, familial bridges, self-forgiveness. His slumped gait straightened faintly; eyes sparked briefly. We, too, must audit: is half-alive outshining nothing? Chase full engagement—flow’s bliss—at energy-time’s crossroads. Sponsor your own awakening; let letters to your future self ignite purpose beyond presenteeism’s haze.

Presenteeism is a condition increasingly plaguing entrepreneurs, a vague malady defined as impaired job performance because one is medically or otherwise physically or psychologically compromised. Is an entrepreneur who is too fatigued or mentally not there for eight hours really better than no one? How about a parent? A spouse? Time has value only in its intersection with energy; therefore, it becomes priceless in its intersection with extraordinary energy – something which I call full engagement. Or flow. Or bliss.

In what areas are you disengaged right now. Whatever the answer, you’re likely to lay a good deal of the blame for this disengagement on external facts – overwork, the time and psychic demands of dealing with aging parents, frequent travel, an unsupportive spouse, not enough hours in the day, debt, not my fault, out of my hands, too much to do, always on the call – but such excuse-making is neither helpful nor accountable.

We enjoy the privilege of being the hero, the final author of the story we write with our life, yet we possess a marvelous capacity to give ourselves only a supporting role in the ‘storytelling’ process, while ascribing the premier, dominant role to the markets, our family, our kids, fate, chance, genetics. Getting our stories straight in life does not happen without our understanding that the most precious resource that we human beings possess is our energy.

The energy principle still holds, and is crucial to ideas in this seminar, too; I maintain that it is at the heart of the solution not only to our individual problems but also to our collective, national ones – our health care problem, our obesity problem, our stress problem, our multi-tasking problem.

In recent years I’ve come to see that, amazingly, the key to almost all of our problems, more fundamental even than poor energy management, is faulty storytelling, because it is storytelling that drives the way we gather and spend our energy. I believe that stories – again, not the ones people tell us but the ones we tell ourselves determine nothing less than our personal and professional destinies. And the most important story you will ever tell about yourself is the story you tell to yourself. (Mind if I repeat that: the most important story you will ever tell about yourself is the story you tell to yourself).

It’s a Wonderful Life, through the life of George Bailey, beautifully illustrates the idea that we are the heroes and authors of the story we live, even though it’s tempting to think that external forces like markets, family, fate, or genetics write that story for us. George often puts himself in a supporting role, feeling trapped by circumstance and sacrifice, while the external pressures seem dominant. Yet, the film reveals that the true power lies in how we use our energy and the stories we tell ourselves about our worth and purpose. George’s energy, initially poured into dreams and ambitions, is redirected repeatedly to serve his community and family, embodying the principle that our personal and collective destinies arise from the stories we choose to live by, not merely those imposed upon us.

The film powerfully demonstrates how misunderstanding or underestimating our role in our own story can lead to despair, as George does when he feels worthless and believes his life has no significance. His crisis of faith and meaning underlines the importance of the stories we internalize about ourselves, especially in difficult times. When George is shown by his guardian angel Clarence what life would have been like without him, the story he tells himself shifts—he realizes that though he saw himself as a victim of fate and circumstance, he is in fact the hero whose actions have shaped an entire community. This transformation underscores the text’s assertion that the most important story is the one we tell ourselves about ourselves, which governs how we gather and expend our energy.

The movie also highlights themes of sacrifice and building a community, tying into the seminar’s ideas about energy management. George sacrifices his own desires, continually putting the needs of others first, exemplifying how our personal narratives often involve a delicate balance between self and others. Yet, this sacrifice is a conscious choice, not a surrender to external forces. His kindness and belief in the importance of every individual reflect a story where love and faith fuel the energy not only for personal resilience but for social cohesion and mutual support. This aligns with the notion that storytelling is crucial to national and collective solutions—from healthcare to stress management—because it shapes how energy is invested in the world around us.

In essence, It’s a Wonderful Life portrays that our lives are an energetic investment, steered by the stories we embrace. George Bailey’s journey encourages reflection on personal authorship: though markets collapse, family demands, and fate seem overwhelming, the narrative we commit to—how we see and value ourselves—determines whether we play a leading or supporting role. Through introspection and renewed faith, individuals can reclaim their heroic story, channel their energy effectively, and transform despair into hope and purpose, echoing the seminar’s core message about life, energy, and storytelling.

Thus, this film exemplifies the insight that the fundamental key to addressing personal and collective challenges lies in correcting the faulty stories we tell ourselves, because it is those stories that ultimately drive our energy and shape our destinies, making the narrative shift from victimhood to heroism possible

So, you would better examine your story, especially this one that is supposedly the most familiar of all. ‘The most erroneous stories are those we think we know best – and therefore never scrutinize or question’ said paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. Participate in your story rather than observing it from afar, make sure it is a story that compels you. Tell yourself the right story – the rightness of which only you can really determine, only you can really feel – and the dynamics of your energy change. If you are finally living the story you want, then it need not – it should not and won’t – be an ordinary one. It can and will be extraordinary.

After all you are not just the author of your story but also its main character the hero. Heroes are never ordinary.

In the end your story is not a tragedy. Nor is it a comedy or a romance or a thriller or a drama. It is something else. What label would you give the story of your life, the most important story you will ever tell. To me that sounds like a hero’s journey.

End of story.

PART ONE

Old Stories

If an idiot were to tell you the same story every day for a year, you would end by believing it – Horace Mann

That’s Your Story?

Slow death.

An uglier two-word phrase it’s hard to find. But if you’re at all like the people I see in the Hero’s Journey & Hero’s Journey seminars, then I’m afraid you understand the phrase all too well.

How did it come to this?

What am I doing?

Where am I going?

What do I want?

Is my life working on any meaningful level? Why doesn’t it work better?

Am I right now dying, slowly, for something I’m not willing to die for

Why am I working so hard, moving so fast, feeling so lousy

Tony Montana arrived in Miami with nothing but fire in his belly—a Cuban refugee dreaming of the American Dream’s simple latte: a decent job, a little cash, respect. “The world is yours,” the billboard taunted, and Tony believed it. He started small, killing for green cards, chainsawing rivals, but each bloody step up the ladder tasted sweeter than the last. From Frank Lopez’s sidekick to kingpin, he built an empire of coke mountains and tiger-striped baths. Yet satisfaction? A ghost. The mansion, the Ferrari, Elvira—wife like a trophy—faded fast. He craved the next grande: more powder, bigger deals, total control.

This is the slow death, the hedonic supersizing that workshop after workshop reveals in raw self-evaluations. Tony’s story mirrors those voices—frustrated, disappointed, trapped in dysfunctional narratives they scribble on day one, unfinished until desperation hits. He had the good and pure once: loyalty to Manny, love for Gina. Achieved? Now they’re chains. The six-figure deals birthed dreams of empires; the mansion begged for a second, a yacht, an island. Each win normalized, dopamine crashed, leaving emptiness. Tony snorted deeper, shot wilder, blind to the treadmill whirring beneath.

In my Power of Your Story seminars, participants echo Tony’s nightmare. They chase “success” like him—salary to six figures, home to vacation palace—only to voice the same hollow frustration. “It doesn’t sound fun,” I hear year after year, worse each time. Tony’s ego took over, plot lost in paranoia. He alienated Elvira with rages, Gina with control, Manny with betrayal. The chainsaw scene’s terror foreshadowed his fragmentation: body and soul diced by endless want. Rebellion against limits? It birthed nightmare—DEA raids, shootouts, sister’s overdose.

Tony’s autobiography, if written, ends in blood: “Say hello to my little friend!” as bullets riddle his mansion. No unknotting, just catastrophe. He supersized goals till fulfillment fled, proving the text’s truth—not everyone dies slowly, but those on this path? Their lives scream dissatisfaction, not living, barely getting by. Workshops show the fix: rewrite the story. Ditch the ego’s infinite hunger for authentic plot—gratitude, purpose beyond stuff. Tony couldn’t; will you? Spot the supersizing early, savor the simple coffee, or join the ranks reading aloud their unfinished tales of regret. Your narrative awaits authorship

Slow death: what a harsh phrase. Is that really what is happening to all those people, the ones who start out contended by what is good and pure in life – a simple cup of coffee, a few seemingly reasonable life goals (a nice salary, say, and one’s own home) – and who , once they have achieved those goals, can’t even be satisfied because they’ve already moved on to life’s next-sized latte (six figure salary, second home, three cars) only to move on to something double-extra grand when that’s achieved, a continual supersizing that guarantees one can’t ever be fulfilled?

Okay. Not everyone I see or hear about is dying slowly. But to judge from the responses I get, workshop after workshop, year after year – and each year it gets worse – whatever it is they’re doing sure doesn’t sound fun. It doesn’t even sound like getting by. I read the frustration and disappointment in their self-evaluations and hear it in their own voices, if and when they’re comfortable enough to read aloud from their current dysfunctional story, the autobiographical narrative they attempt to write the first day at the Power of Your Story, but usually don’t finish until the night before our last day together.

Charles Foster Kane started with the simple latte of life—a boy in the snow, sledding on Rosebud, dreaming pure joys amid Colorado’s chill. His mother traded him for security to Thatcher, the banker who dangled education and fortune. Kane resisted, wielding that sled like a shield against the world stealing his innocence. Yet the American Dream whispered promises: a newspaper, power, influence. He seized the Inquirer, crusading for the little guy, filling pages with zest. Readers flocked; satisfaction bloomed. But contentment? Fleeting. The grande called—a political run for governor, Emily as trophy wife, a mansion to dwarf rivals. Each victory normalized, hunger gnawing deeper.

This is the slow death I hear in workshop after workshop at Power of Your Story. Participants arrive content once with modest goals—a steady salary, cozy home—like Kane’s early Inquirer days. They achieve, celebrate briefly, then supersize: six figures, second properties, fleets of cars. Frustration mounts in their self-evaluations, voices cracking as they read unfinished autobiographical drafts on day one, delaying till the last night. Kane’s tale mirrors theirs. Post-election scandal—courtesy of his rival—shattered his governor bid, but he pivoted to Susan, the singer from the nightclub. Opera lessons, tours, a career supersized on his dime. Headlines hailed her “success,” yet her voice cracked like his soul. Pills piled up; a suicide bid halted the charade. Still, he pushed grander: Xanadu, his pleasure dome, a warehouse of looted wonders—statues, art, European castles shipped whole.

Year after year, the responses worsen. “It doesn’t sound fun,” they confess, echoing Kane’s hollow empire. Xanadu sprawled endless, mirrors multiplying his image into infinity, statues staring back in judgment. He collected obsessively—Egyptian relics, Venetian gondolas—each acquisition a bigger latte to quench the void. But love soured: Emily divorced him over infidelity; Susan fled after he smashed her dressing room, barbiturates spilling like his wasted energy. Manny-like friends? Bernstein and Leland faded, loyalty bought then betrayed. Kane’s energy, once vibrant in newsroom brawls, drained into isolation. Power motive thrummed in Herrmann’s score, Dies Irae condemning his ruthless climb—tritones twisting like his heart. Rosebud’s melody, hopeful fourths falling, haunted as childhood’s ghost.

In seminars, I see Kane’s dysfunctional story replicated. They chase external wins, blind to the treadmill. Kane’s “Declaration of Principles”—fighting corruption—devolved into scandal-mongering for circulation. Marriage to Emily? Political alliance supersized to control. Susan? Ego’s puppet, her failure his mirror. Each phase birthed bigger voids: Inquirer to media empire, wife to mistress, home to Xanadu. Workshop voices reveal the toll—stress, obesity, health crumbling under multitasking myths. Kane aged into a tyrant, ranting at empty halls, infinity mirrors mocking his solitude. No joy in the palace; just echoes. His energy, squandered on supersizing, left a shell. Reporters chased “Rosebud” post-death, piecing fragments—mother’s boarding house, sled in flames. The missing piece burned, like lives half-lived.

Kane’s “No Trespassing” gates sealed his fate. Power isolated; possessions mocked. He died clutching a snow globe, whispering “Rosebud”—that simple sled, pure joy before Thatcher’s theft. Not wealth consoled, but lost innocence. Workshops prove not all supersize to death, but those who do? Their narratives scream disappointment, barely getting by. Rewrite now: savor the coffee, not the venti abyss. Kane couldn’t finish his story; his draft incinerated. Yours awaits bold authorship—trade grand illusions for genuine plot, or join the slow death parade, voices fading in regret. Spot the supersizing; reclaim your energy before Xanadu becomes your cage.

As the Power of Your Story seminar progresses and people’s defenses start to melt away, I hear more and more of these stories. By almost any reasonable standard, these stories exemplify failure; in many cases, disaster. There is no joy to be found in them, and even precious little forward movement. In every workshop, nearly everyone has a dysfunctional story that is not working in at least one important part of his or her life: stories about how they do not interact often or well with their families; about how unfulfilling the other significant relationships in their lives are; about how – despite all that extracurricular failure – they’re not even performing particularly well at work, or, if they are, about how little pleasure they gain from it; about how they don’t feel very good physically and their energy is depleted.

On top of all that (isn’t that enough?), they feel guilty about their predicaments.They know, on some almost buried level, that their life is in crisis and the crisis will not simply go away. Their company is not going to make it go away. And so they wake up one morning to the realization that the bad story they for so long only feared has finally become their life, their story. Not that this development is their fault. No. Nor is there a heck of a lot to be done about it.

It is a competitive, cutthroat world out there

God knows, I want to change but I simply can’t. I’ll get eaten up and beaten by someone who’s willing to sacrifice everything.

The world moves faster today than it did a generation ago

What am I supposed to do – quit my job?

These are the facts of my life. There’s nothing I can do about them.

My life is a known quantity; so why mess with it even if it’s killing me?

Let me repeat that one: …… even if it’s killing me.

People don’t need new facts – they need a new story.

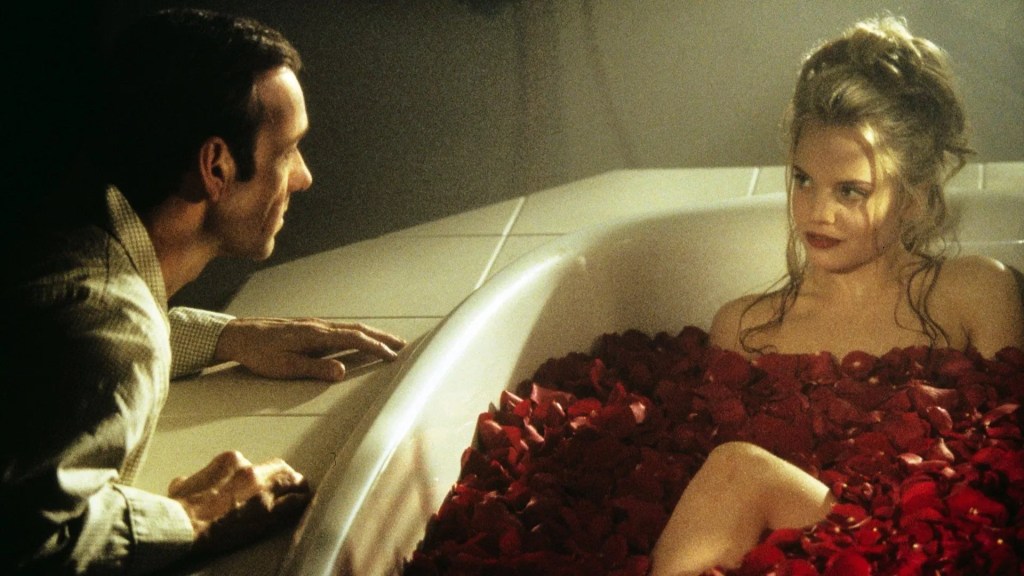

The Purpose of Seeing: The Awakening in American Beauty

Lester Burnham’s story begins the way many purpose stories do—inside a life that looks complete but feels lifeless. A comfortable house, a career, a family, routines finely tuned and utterly empty. He is not lost in chaos, but in numbness. His days move smoothly, unexamined, until one quiet realization disturbs the surface: “I have become invisible in my own life.”

That recognition—painful, almost embarrassing—is where purpose begins. It rarely enters through grand events, but through fatigue with pretending. Lester doesn’t wake up to some new opportunity; he wakes up to the truth that he has been asleep for years. He begins to wonder what it means to actually live, not merely function.

The First Stirring of Choice

Every story of purpose begins with disobedience. For Lester, it starts small—a refusal to keep performing the part written for him. He begins to question everything that feels automatic: his job, his marriage, his endless compromises. It’s not rebellion for its own sake, but the instinctive reach for authenticity.

We are taught to measure success by security, yet purpose resists containment. Lester’s first steps toward freedom are clumsy, sometimes selfish, sometimes beautiful. He quits, he laughs, he remembers music, movement, desire. What the world calls crisis, his soul calls renewal.

The Illusion of Freedom

Like many travelers on the road to meaning, Lester mistakes liberation for purpose. He confuses “doing whatever I want” with “becoming who I am.” Yet behind his apparent recklessness blooms something more gentle—a reawakening of wonder. Mowing lawns, lifting weights, driving at night with the windows open—these moments, simple and unpolished, return him to presence.

Purpose often begins beneath the surface of joy. It’s the quiet sense that being alive, truly alive, is enough. For Lester, beauty breaks through not as perfection but as awareness—an invitation to see the sacred inside the ordinary.

The Mirror of Others

Around him, every other character reflects a fragment of this same hunger. His daughter, searching for identity; his wife, trapped in control; the boy next door, finding magic through the camera lens. Through them, the film whispers that we all live behind walls of fear—different costumes, same prison.

Ricky’s perspective—his ability to find beauty in decay—becomes Lester’s teacher. What is ugly and mundane, he sees as alive. Watching him, Lester finally grasps that purpose is not something to acquire but to perceive. The world hadn’t gone dull; he had simply stopped noticing.

The Moment of Grace

At the end, as his life narrows to a single instant, Lester finds what he was chasing all along: presence. He has rediscovered love for his daughter, compassion for his wife, and a quiet reverence for existence itself. That final smile—tranquil, unafraid—is the subtle mark of a man who has reclaimed his purpose, not by adding anything new, but by remembering how to see.

Purpose, in his story, is vision restored: the ability to witness life as gift rather than burden. American Beauty reminds us that beauty is not an adjective but a state of awareness. It waits beneath the noise of ambition, the exhaustion of pretending, the clutter of control. Once we pause to notice, even a plastic bag lifted by the wind can reveal the meaning we thought we’d lost.

Is Your Company Even Trying to Tell a Story?

We’ve examined the corporate story the worker hears. Let’s see what story the company is typically telling.

First they need you and you need them. (Ideally, they also want you and you also want them, but that may not be part of your company’s story). The typical company is saying that the fast-paced business world being what it is – what with globalization and outsourcing and downsizing and sustainability and AI and synergies and streamlining – it must make increasing demands on your life. Keep swimming or die. Which means longer hours for you, ergo less time for your family and yourself. It means holding meetings during lunch or before or after the workday proper, which essentially kills your chance to exercise and stay in shape. (and let’s just order in any food that’s fast during meetings to maximize efficiency). Oh, right: and while all this is going on, the company – continually stressing its imperative to move forward if it is to survive at all – also demands that you frequently change directions, reinvent the very way you operate, completely alter how you conduct business.

Everyone who likes that story, raise your hand.

Older workers, in particular – those who have seen it all before – are likely to undermine the story for such a company. So, too, anyone else who fears that he or she may be easy to eliminate, or may have a diminished role in the transformed company. To these employees the story their company is telling may be exciting in the abstract, or to investors, but it’s potentially humiliating for them. Among these workers, suspicion, cynicism and distrust run rampant. While the defiant worker publicly may appear vested in the change process, privately he tells himself: New thinking be damned. He works subversively to undermine the new directive. He knows that, for the new initiatives to take, everyone must embrace them. Not him. He will go through the motions but he is not going to make any real course corrections.

And so, like a dinosaur, he moves closer and closer to extinction.

The employee loses and the company loses as well. Entire organizations have been undermined by storytelling that excludes a significant portion of their workforce. Failure to align the evolving corporate story with the aspirations of the individual employees, up and down the workforce – the very ones who have been enjoined to help write that new, improved story – has systemic implications. Athletes routinely give up on playing hard for coaches they deem excessively punitive or inconsistent; the bond of their mutually aligned stories – to win a championship – is undermined because the coach’s story does not seem to allow for the inevitable particularities of any individual athlete’s story. Mutiny is not just what happens when ship captains indefensibly change or robotically stick to the rules but also when CEO’s and schoolteachers do it. Organizations have been undermined by refusing to alter their story when it clearly wasn’t working.

The Social Network tells the story of the rapid rise of Facebook, a story representative of many modern companies’ demanding and fast-changing narratives. Mark Zuckerberg starts as a Harvard undergraduate with an idea born from frustration and ambition. The company’s implicit story to its people is relentless growth and reinvention to survive the cutthroat, ever-accelerating tech world. The demands on Zuckerberg and his team escalate quickly, their lives consumed by coding, negotiating, and scaling, with little room for personal connection or reflection.

From the start, Zuckerberg’s world is marked by conflict in relationships—his breakup with Erica Albright, the fraying of friendship with co-founder Eduardo Saverin, and clashes with the Winklevoss twins who accuse Zuckerberg of intellectual theft. The fast pace of innovation in Facebook’s story leaves no time for reconciliation or trust-building. The energy they invest drives incredible success but simultaneously saps their personal lives and moral compass.

Older figures or partners in the narrative, like Eduardo, become marginalized and betrayed as corporate priorities and ambitions overshadow loyalty and fairness. With new leadership and investors like Sean Parker stepping in, the story focuses on scaling and domination, often at the cost of human connection. The company’s drive to constantly evolve breeds suspicion, distrust, and legal battles, reflecting the toxic dynamics that many workers experience in the high-pressure corporate world.

The climax is bittersweet: Facebook becomes a global powerhouse, yet Zuckerberg ends up isolated, alone, and yearning for the genuine connections he sacrificed. The story underscores how the company’s relentless demand for reinvention and success paralleled his personal alienation.

Zuckerberg’s tale offers a mirror. The corporate story often demands that we “keep up or be left behind,” driving burnout and fractured relationships. What’s missing is a new story—one that values people as much as profits, that balances ambition with humanity. Changing facts like market dynamics won’t suffice; shifting the story we tell ourselves and each other about work and value is key to restoring energy, connection, and purpose.

The Social Network illustrates the cost of a corporate story without heart—a cautionary tale urging companies and individuals alike to rewrite their narratives for sustainable success and human flourishing.

If alignment of stories, yours and your company’s, is to be achieved – and I believe it’s neither as lofty nor as complicated a task as it may sound – then it is ideally generated both from top down (the company side) and bottom up (the workers side). But let’s not get carried away. For our purposes, we’ll presume zero input form the company. It is, after all, corporate culture.

That means the burden to change stories is on you.

Presenteeism

What if the most important adventure of your working life was not about the projects you complete, the titles you hold, or even the outcomes you deliver—but about the story you tell yourself? What if the office, with its familiar routines and relentless pace, is both your crossroads and your call to adventure?

Those who know me understand I see life and work as journeys—epic quests each of us must undertake. Every working person is a hero in the making. And every workplace challenge is a shadowy threshold, begging us to re-examine the story we live by—and the roles we choose.

In my journeys with creative professionals, entrepreneurs, leaders, and artists worldwide, I notice a repeating theme: too many of us are living by default stories, not the ones we would choose if we remembered we had the pen in our hand. Even the most ambitious, purpose-driven individuals fall prey to this trap.

We tell ourselves stories like:

- “I am valuable because I am always here.”

- “If I slow down or admit I’m struggling, I’ll be replaced.”

- “To be a hero is to put others before myself, no matter the cost.”

These are powerful myths, but not always true or empowering for the modern workplace hero. They lead us straight to the quicksand of presenteeism, where showing up becomes a prison, not a purposeful journey.

The First Threshold: Awakening to the Call

Every hero’s journey begins with a call to adventure—a crisis that shakes up the old world and offers a chance, however frightening, for transformation. Presenteeism is this crisis. What if you saw your own disengagement or declining health not as a personal failing, but as a summons? A moment to examine the story you’re living.

Are you actually answering your call, or are you stuck reliving someone else’s tired script?

Pause for a moment at your desk. Close your eyes. Ask: What is the true story I’m living here? Am I the weary warrior constantly pressing on, or the resourceful hero who knows when to rest, renew, and return with deeper gifts?

The Purpose of Awakening: Neo’s Journey Through The Matrix

When I think of Neo’s story, I don’t see machines or battles first. I see a man sitting quietly before his computer, haunted by the feeling that something essential is missing. That itch—that faint pulse of discontent—is the sound of purpose calling. It begins as a question: What is real? What am I meant for? Every seeker starts there, in the tension between what the world shows and what the heart suspects.